1970

November 14, 20171972

November 14, 2017With the addition of the newly founded state of Bangladesh in March 1971, he completed a work in progress begun in 1967, a collection of geopolitical maps. The final work, titled Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967, made on copper plates, engraved after the model of his tracings on paper, was exhibited at the Galleria Sperone in summer. In autumn an edition printed on paper was issued.

Portrait of Giovan Battista Boetti, 1743-1794

Meanwhile, in late March AB left for Afghanistan and stayed there several weeks. This was the beginning of a ritual of making two visits every year which continued up until 1979. He chose Afghanistan for various convergent reasons. One was that an ancestor of his, the Dominican friar Giovanni Battista Boetti (born in Monferrato at Piazzano in 1743) had been sent to Mosul at the head of the Evangelical Mission for Asia Minor. Subsequently he converted to Sufism, Persian Islamic esotericism, and was considered an apostate by the Roman Church. Calling himself the Prophet Mansur he became one of the heroes of the resistance against Tsarist imperialism in the Caucasus, with risings from Armenia to Chechnya. Two centuries later there appear extraordinary parallels between the two Boetti, both in the splitting of their identities and their geopolitical interests.

Two months before setting off for Afghanistan, AB duplicated the sole existing portrait of Giovanni Battista Boetti as a young Dominican friar and added it to the catalog of the group exhibition “Formulation” (Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover), next to another “indirect self-portrait”: his own profile in a very Pop version in a wooden silhouette, painted in 1970 by the Turin-based painter Pietro Gallina, which the artist loved to present in exhibitions among his own works. AB gave other possible reasons for going to Afghanistan:

“My interest in distant things wasn’t strong when I became an artist. I thought of travel in strictly personal and hedonistic terms. The principal factor in its allure was very precise: I was fascinated by the desert, and not just the natural desert. In an Afghan house for example, there’s nothing: not a single piece of furniture, hence none of the objects that are usually placed on furniture… What attracted me most was the blankness, the civilization of the desert. Afghanistan is a country of mountains, where villages are built on mountainsides so as not to waste the fertile land in the valleys. Nothing is added to the landscape. They clear the stones and use them to build their cube-shaped houses, as in Paul Klee’s watercolors, and they lop the branches off a tree to make the loadbearing structure.”

One Hotel in Kabul, courtesy Archivio Alighiero Boetti

In Kabul he had two squares of fabric embroidered with two dates, 11 luglio 2023 – 16 dicembre 2040, based on the diptych made previously in two versions, one of lacquered wood and the other brass.

This was the first of the embroideries he commissioned from Afghan women. On returning to Italy, in May he exhibited the diptych in the brass version at “Arte Povera – 13 artisti italiani,” a group exhibition held at the Munich Kunstverein. For the catalog AB asked (in vain) for the four pages at his disposal to be replaced by a single white sheet of industrial paper, of the equivalent weight, with nothing but his name printed on it.

Meanwhile, on 4 May, by sending the first telegram (“2 days ago it was 2 May 1971”) he began an essential work: the sequence of telegrams that was to form the Serie di merli disposti a intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muraglia (“Series of battlements arranged at regular intervals along the ramparts of a wall”). It is based on the rule of doubling the time intervals after the initial date (2, 4, 8, 16…). AB immediately designed a special display case to contain the greatest number of telegrams that could be sent in his lifetime. The fourteenth and last one would be sent by the artist in 2017, when he would be seventy-seven years old. The space for the last of the “battlements” was left empty in the “wall.”

At the end of summer, in the exhibition curated by Achille Bonito Oliva for the International Theater Fes- tival in Belgrade, Boetti repeated his two-handed mural writing performance.

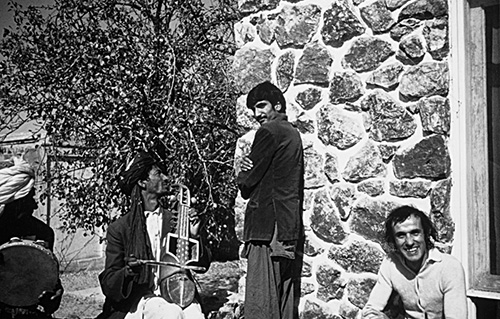

Alighiero Boetti with musicians at One Hotel in Kabul in 1971, courtesy of Alighiero Boetti Archive

In September AB returned to Kabul, taking some pieces of linen, on which he had impressed a map of the world by photographic projection, colored according to the national flags (like the Planisfero politico, his earlier work on paper dating from 1969). The young ladies at the Royal School of Needlework took a whole year to complete the large Mappa and six months for the smaller ones.

At the same time further maps were commissioned from a family in the village of Istalif. The preliminary work for the embroidery was always done in Italy.

Every minor detail was specified: the forms of the continents and the boundaries of states, the forms and colors of the flags, the changes over the years to national boundaries and flags to reflect political changes—even variations in the rules of the projection of the earth’s curvature. In the early years the date registered on the embroidered selvage marked the completion of the embroidery in Kabul. After ’79 the date was generally inserted in Rome together with the mapping, so it marked the beginning.

The postal works with Italian stamps were followed by the first with stamps from Afghanistan.

During his stay in the country he created One Hotel, in a small mansion house with a garden in the Sharanaw residential quarter of Kabul. Its address was Zarghouna Maidan. An initiative of this kind was fairly simple under the monarchy of Zahir Shah. Its management was entrusted to the young Gholam Dastaghir, who had some [experience in the business. The hotel shared the fate of the country. It had to close a few years later, long before the official Soviet occupation.

Returning from Afghanistan, on 24 September AB exhibited at the Italian section of the Biennale de Paris, curated by A. Bonito Oliva. At its close, the same works (Viaggi postali, Dossier postale and Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967) were exhibited in Rome at the Incontri Internazionali dell’Arte, in the group section titled “Informazioni sulla presenza italiana.”

The 99 Postal Dossiers completed in Milan in 1971, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In the same period AB began to produce works written in blue ballpoint pen on white cardboard which played on his name and identity: AB, ALIGHIERO BOETTI MADE IN ITALY, ABEEGHIIILOORTT, AELLEIGIACCAIEERREOBIOETITII. Then finally he began to split his identity in two by inserting “and” in his name, hence writing it “Alighiero e Boetti.” In this way he expressed the equivocation created by the photo of his twin selves in ’68. Various statements he made show that the decision was a true conceptual operation:

“I always worked on the half and the double, and the missing unity—something that never exists. I used this mechanism in various works, including one like my first name and surname by putting ‘and’ between them… They become two people, and not just linguistically but really, because some people actually think I have a twin—and it’s true.”

Boetti created the language square Ordine e disordine on paper in 1971. Its material composition differed from the square titled 1970, sprayed with paint on paper. It was created as a negative, the color being sprayed over the surface but was covered by a template bearing the lettering. Apart from the formal composition of sixteen letters, the concept conveyed by the two words was of fundamental importance in the artist’s thought:

“I worked a lot on the concept of order and disorder, disordering order or ordering certain kinds of disorder, or presenting a visual disorder that was actually a representation of mental order. I think everything contains its opposite, we always have to seek one in the other: order in disorder, the natural in the artificial, shadow in light and vice versa.”