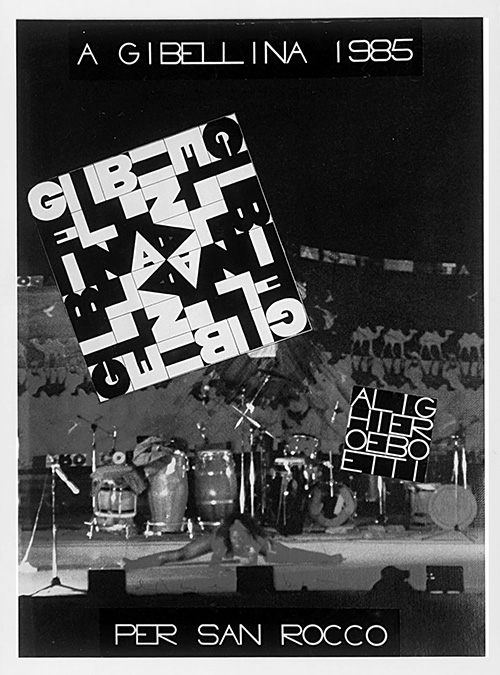

CHRONOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY

Chronological biography written by Annemarie Sauzeau for the General Catalog

1940

Alighiero Fabrizio Boetti was born on 16 December, at 5 Corso Trento in the Crocetta district of Turin.

He came of an aristocratic family originally from Fossano (Cuneo). The Counts Boetti had lost their landed estates in the nineteenth century and the following generations practiced the legal profession in the city.

Alighiero Boetti with his parents, 1942-1943

His father, Corrado, was a lawyer. His mother, Adelina Marchisio, had been a promising violinist but devoted herself to domestic life, while his sister Elena had a significant career as a pianist and teacher at the City Conservatory of Music. With his elder brother Gualtiero, Alighiero passed an unhappy early childhood, having been evacuated with their mother to Giaveno in the countryside until the war’s end, while their father was at the front.

His adolescence in the postwar years was even more difficult. His parents separated in 1949 and he grew apart from his father, who offered him very little emotional or practical support. Alighiero attended Michele Coppino Primary School, the Germano Sommeiller Technical School. He then enrolled very unwillingly in Business School but soon dropped out.

1955-1961

Boetti is an autodidact. Pavese, Montale, Mann, Faulkner and above all Herman Hesse (whose complete works he read) were some of the authors who meant most to him.

Turin at the time was a highly stimulating city with an international outlook, largely due to the Einaudi publishing house and certain other outstanding points of cultural focus, such as the Galleria Galatea run by Mario Tazzoli. Here the young Boetti discovered Tantric art. His initiation into contemporary art came at seventeen in Luciano Pistoi’s Galleria Notizie, where he saw watercolors by Wols, works by Fontana, paintings by Gorky and Rothko, drawings by Henry Michaux and discovered Cy Twombly in 1963 (a year also notable for Balla’s first major retrospective at the Galleria Civica).

In around 1960 AB painted a number of works in Art Informel style using oil or tempera on canvas or cardboard. “At twentytwo he did not yet see himself as a painter, but his vocation as an artist was not in doubt. His masters were Matisse, the Balla of the abstract exercises and watercolors, Wols and Nicolas De Stael, who he regarded as the Cesare Pavese of painting. But he believed the greatest was Paul Klee.”

“I actually first became interested in the exotic when I was fifteen, thanks to Paul Klee’s Moroccan watercolors. He was born on 16 December like me,and this made my adolescent identification easier. Very ingenuously, I had ‘copied’ those watercolors before I knew who they were by.”

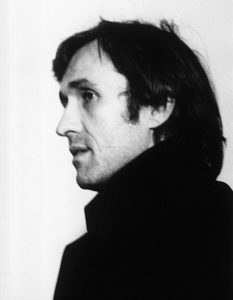

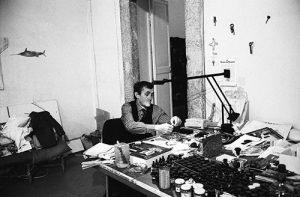

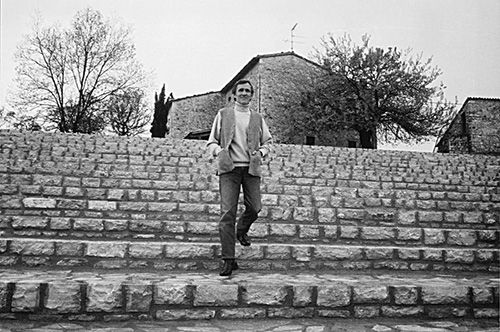

Alighiero Boetti in Turin, 1960. Courtesy Agata Boetti

At the same time, to make a living he set up a business and ran it for some years. He had got to know Provence through Delfina Provenzali, a translator and friend of the poet André du Bouchet (Nicolas de Stael’s son-in-law). In the village of Vallauris he bought ceramics by Picasso and other artists and sold them in Italy. It was here that in 1962 he met Annemarie Sauzeau, a young English teacher, who became his wife in 1964; they remained married until 1987.

1962-1964

Boetti moved to Paris in autumn 1962 and stayed there for most of the next two years. He saw at first hand the abstract lyrical works of De Stael, the tactile works of Dubuffet and Fautrier, and calligraphic Zen painting from Japan in a historical exhibition at the museum of the Petit Palais. He discovered the concept of André Malraux’s multicultural “imaginary museum” through the famous book published by Skira (reprinted many times from 1947 on). He absorbed it to the point where he confused it with the later exhibition organized in 1973 at the Maeght Foundation on the same subject.

“There was also that exhibition organized by Malraux in Paris in the early sixties: the ‘Imaginary Museum’ or something of the sort… He had chosen the finest pieces from different museums all over the world, Sumerian art, Egyptian, Khmer sculpture… I clearly remember an Assyrian statue in white marble with eyes in lapis lazuli.”

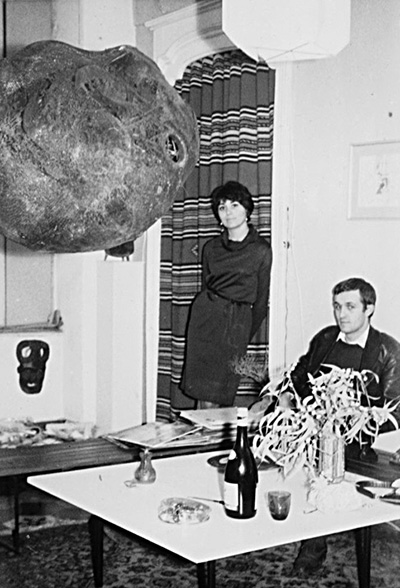

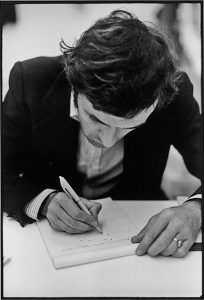

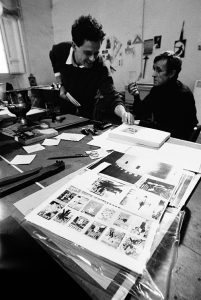

Alighiero Boetti and Annemarie Sauzeau, 1964

Lacking a studio, he concentrated on “chamber works”: drawings in India ink on kleenex and “combustions” of small boxes of matches, perhaps with an allusion to the Peintures-feu of Yves Klein, who had recently died in Paris (May 1962). In early ’63 he learned the technique of engraving in Johnny Friedlaender’s studio. Starting by using black ink he eventually developed a sophisticated polychromy. In the studio he also met the Cuban artist Ramon Alejandro, with whom he formed a close and lasting friendship. He read Marcel Granet and discovered the ideas of Gaston Bachelard. Piero Manzoni died aged thirty in Milan.

By autumn ’64 he had returned permanently to his apartment-studio on Via Principe Amedeo in Turin.

He still continued to do engravings, but his main focus was on large drawings in pencil on cardboard.

Alighiero Boetti at the Friedlander studio in Paris, 1963, photo by Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti

These works were subtly modulated from black to grey, as if they were engravings done with variable concentrations of ink. Unlike the early Parisian examples (non-figurative organic forms), he was now producing cold mechanical outlines traced using old Fiat engine gaskets or vaguely Pop comic strip imagery, with inscriptions similar to labels.

He also produced threedimensional objects, starting from scavenged pieces of sheet metal. He welded and spray painted them, leaving a “viewfinder” that traversed the chunks of metal.

“Among these objects suspended from the ceiling at the height of the eyes like a viewfinder, I can remember a piece of the bodywork of a van, with the side view mirror and the seat repainted a golden yellow.

1965

AB moved on to a new kind of drawing in India ink, doing black Chinese shadows and silhouettes: simplified outlines of combs, tumblers and bottles, industrial equipment, desk lamps, microphones, still and movie cameras. Boetti exhibited these drawings for the first time in 1981 in Paris and ten years later at his retrospective in Bonn.

“With microphones, lamps and viewfinders, still cameras and movie cameras, I wanted to create situations that engaged the viewer in a new dimension. Of the theater, in short.”

In the summer he began working in a small studio, a former porter’s lodge close to his apartment in Via Montevecchio where he had moved. These first non- pictorial works turned on the energy of “things,” which broke through the mural plane. Subsequently they were destroyed by the artist himself and only some sketches of them remain.

In conversation with Mirella Bandini in 1972, he said:

“The first was a masonite panel from which emerged a fist, a cast of my own, while I was on the other side of the wall. The idea was the energy of a wall opening out… Then I did other panels, a hand offering a chair; the chair was cut in half, with one part entering the painting.”

1966

On the art scene in Turin, AB tended to keep to himself. He produced numerous minimalist works. Some, in particular those using light installations which shortly preceded Ping Pong and Lampada annuale, were only exhibited between 2002 and 2003. Others, chosen by the dealer Christian Stein, formed the core of his first solo exhibition in January ’67.

“In the winter of ’65–66 I prepared an immense number of works and projects. By about May ’66, convinced it was impossible to use everyday practical objects, I tackled some new abstract works. They were lines on the ground, two flashing lights, a plexiglas panel suspended from the ceiling, some daises, sloping floors and even a well! There was still something of the theater in my need to put people in situations, even to amuse them.”

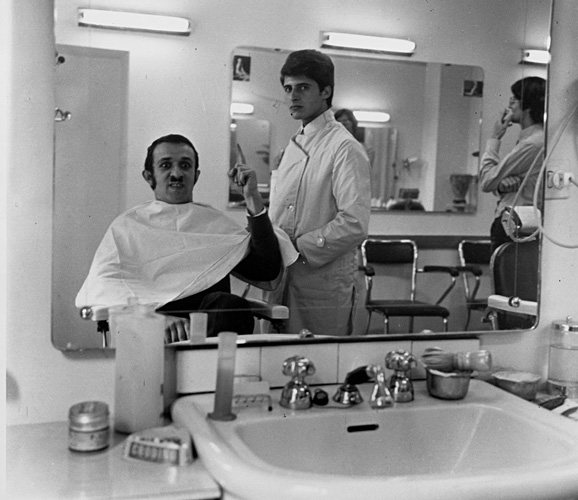

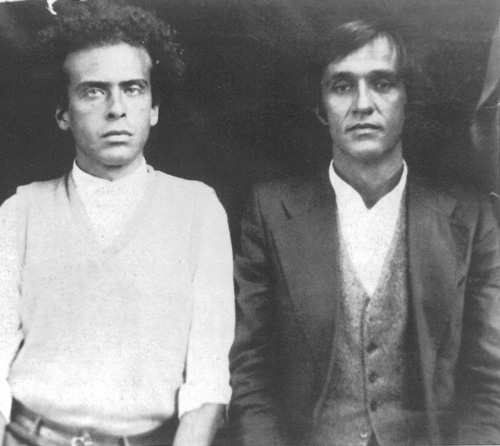

Alighiero Boetti with Giulio Paolini from the barber, photo by Anna Piva Paolini

This year AB began to frequent the avantgarde galleries run by Gian Enzo Sperone and Christian Stein, where he met some young Turin-based artists, including Mondino, Gilardi, Piacentino, Paolini and Pistoletto.

“I was on good terms with Pistoletto and saw Gilardi and Piacentino every so often, but we moved in different circles. Today, looking at things from a distance, I’d say everything came from that group. And Pascali, when he did the exhibition with the Cannons in ’66 at the Sperone Gallery, it was in Turin that he was most appreciated, and the same is true of Fabro.”

With Giulio Paolini, however, Boetti immediately formed a close relationship. Paolini himself recalled it in these words: “Alighiero and I met in ’66. There was immediately a special relationship, different from that between colleagues which I had with other artists from Turin. With him there was a friendlier and more confidential feeling, more open.”

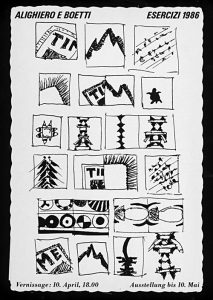

1967

19 January, Galleria Christian Stein: opening of Boetti’s first solo exhibition. All the works exhibited dated from the previous year: for example, Rotolo di cartone ondulato, corrugated cardboard in the form of a ziggurat, Lampada annuale, which lit up once a year for eleven unpredictable seconds, Scala, Catasta, Sedia, Tubi PVC, Mimetico, Zig Zag and the diptych Ping Pong.

“Knowing of innumerable events that happen without our participation and knowledge, because of the pure impossibility of space and time, I was prompted to make the Lampada annuale as a theoretical-abstract expression of one of the infinite possible events, the expression not of the event but of the idea of the event… While the Lampada annuale was a totally literary work, of Catasta, Tubi or Cartone ondulato, all I have to say is: it’s a stack, it’s a roll of cardboard pushed up from inside, it’s a bundle of tubes and so forth.”

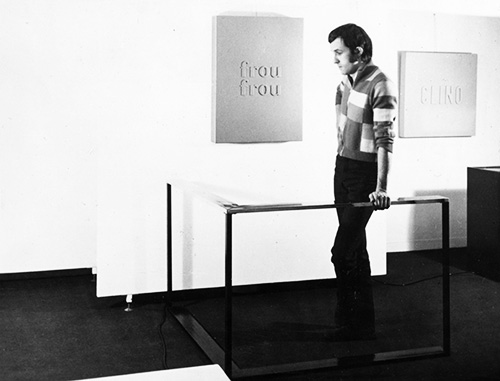

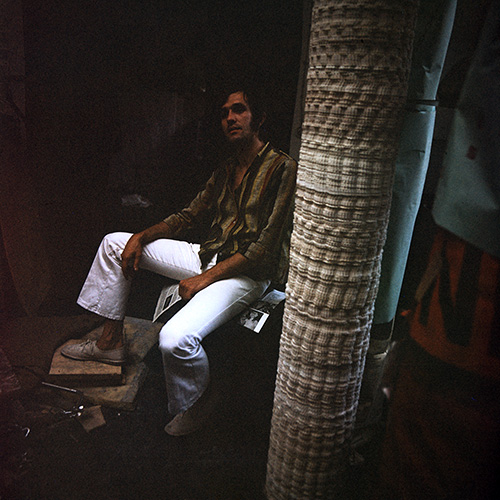

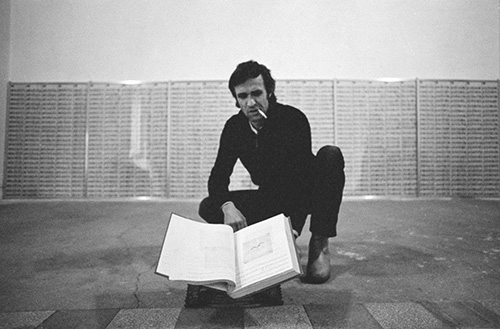

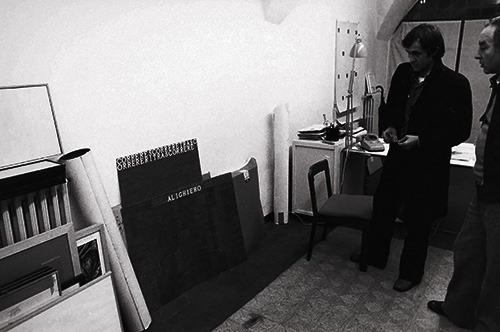

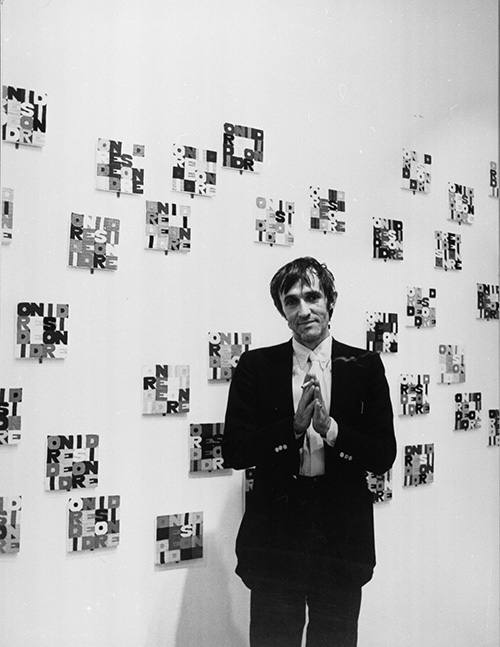

Alighiero Boetti at the Christian Stein gallery in Turin, photo by Paolo Bressano

In the profusion of ideas, gestures and objects of ’66, there was already an obsession with writing and two dimensions, with various panels devoted to language: stiff upper lip, the thin thumb, CLINO, frou frou.

“Sculpture or the object never interested me.”

All the more so in ’67 Manifesto was totally conceptual, and even the multiple Contatore. This first solo exhibition was reviewed by Tommaso Trini in two articles, in Domus (February) and Bit (March). Paolo Fossati reviewed the exhibition twice, in the journal Flash and the newspaper L’Unità.

In the spring following the exhibition, Boetti began what he called “panels of colors.” The raised wording, with a tautological effect, gave the name of the industrial color that had been sprayed across the surface as if it was a car body.

“In the case of Beige Sahara and seven or eight other colors, I wrote ‘Beige Sahara’ and used the color Beige Sahara.”

In this period he moved into a new studio, larger and brighter, on Corso Principe Oddone. Between the first exhibition at the Galleria Stein and his second solo show at La Bertesca in Genoa in December, he took part in all the early group exhibitions of Arte Povera in Turin, Milan and Genoa, especially “Con/temp/l’azione” curated by Daniela Palazzoli and held in the three Turin galleries Il Punto, Sperone and Stein, and “Le parole, le cose – Fluxus: Arte totale” held at the Galleria Il Punto and the Teatro Stabile.

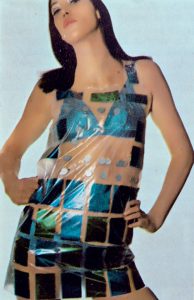

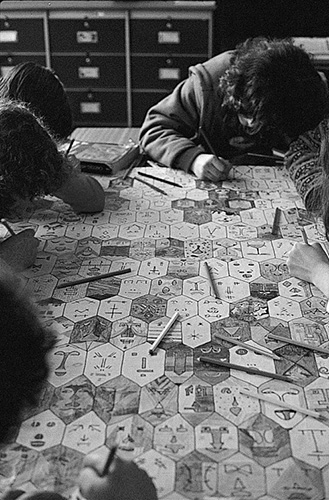

Dress designed by Alighiero and Annemarie Boetti, at the Pipier club, Turin, courtesy of Annemarie Sauzeau

In April Rotolo di cartone ondulato was added to the Museo Sperimentale d’Arte Contemporanea at the Galleria d’Arte Civica in Turin. Among the texts in the catalog, the essay “Situazione 67” by Germano Celant analyzed Boetti’s work in these terms: “The new monumental forms, instead of being made of natural materials—marble, granite or other types of rock—are made from artificial materials, steel, formica, plastic, plexiglas… Definitely more impressive and “present” are Boetti’s piles of tubes in masonite and in plastic, tactile aggregates of objects, on which the mere act of accumulation confers an independent and essential value, a sort of aesthetic register of elements in the pure state, a rejection of the problem of form.”

On 16 May, AB took part, with Annemarie Sauzeau, Piero Gilardi and Elio Colombotto-Rosso, in a “Beat Fashion Parade” held at the Piper Club in Turin, designed and organized by the architect Piero Derossi.

The “collection” by Boetti consisted in clothes made from transparent colored plastic containing heterogeneous materials.

In June he began a work in progress, Formazione di forme. The first “form” was that of the territories occupied by Israel extending as far as Egyptian Sinai, which AB traced from the newspaper La Stampa of that date. This and the following geographic forms, recorded on paper, always dated and taken from the newspaper, were incised in ’71 on twelve copper plates with the title Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967.

In July he took part in the group exhibition “Confronti” at the Galleria Christian Stein. On display were works by Fontana, Klein, Manzoni, Fabro, Kounellis, Lo Savio, Merz, Mondino, Paolini, Schifano and Twombly. In the summer he spent a long period in the Cinque Terre: at his home perched above the sea in the village of San Bernardino between Vernazza and Corniglia, he experimented with the possibilities offered by polaroid shots of his own body, taking self-portraits in Gran bacino and entrusting the shot of San Bernardino to his friend the fashion photographer Robert Cagnoli.

27 September–20 October, Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa: group exhibition “Arte povera-Im spazio” curated by G. Celant. AB was present in the Arte Povera section with a new Catasta, made up of twelve pieces instead of the previous thirty-four. This was the actual occasion when the Celant coined the Grotowskian concept of “poor art.” Of Boetti he wrote: “… The mode of definition is reduced to the mode of acting and being. Hence Boetti’s gestures are no longer an accumulation, a montage, wooden joint and stack… So here we have ‘figures’: the Castata as accumulation, the joint as joint, the cut as cut, the stack as stack, mathematical equations of real = real, action = action.” Subsequently, in the article “Arte Povera, appunti per una guerriglia” in Flash Art, Celant returned to the subject and described Boetti as an artist who “reinvents the inventions of man.”

Alighiero Boetti in his studio in Turin, via Principe Oddone, photo by Mario Ponsetti, 1967

In December he had a solo exhibition at the same Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa, with new works, among which different versions of Mimetico and three-dimensional works, all reproduced in the catalog, the

first important publication to deal with AB. It contained farsighted essays by G. Celant, H. Martin and T. Trini. Thirty copies of the catalog were signed, numbered and accompanied by a drawing by the artist.

Other copies had four (six?) silk-screen prints in fifty copies: they were a posteriori industrial plans not only for the works exhibited but also other works like Rotolo (1966) and Catasta (1967). The prints were made by the Genoese art printer Rinaldo Rossi and marked the start of his continuing collaboration with Boetti. 1967 was also the year AB produced Dama (“Chechers”), a wooden checkerboard made up of movable blocks with various symbols punched on them, so they could be recomposed by pairing like with like as in dominoes.

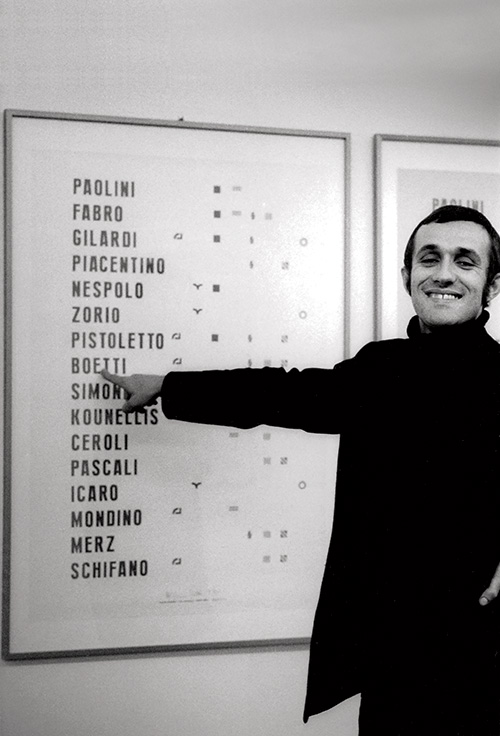

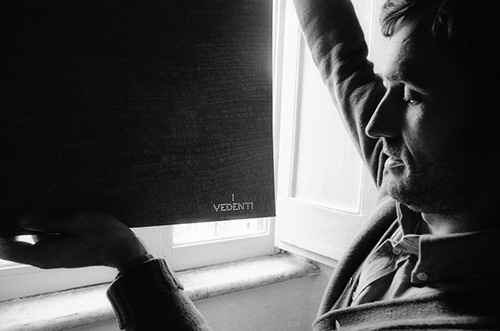

With I Vedenti (“The Sighted”), a low relief in plaster, AB explored the significance of the sense of sight but garbled it by appropriating the language of the Other, of the blind. Finally there was Manifesto, a conceptual work which presented a list of sixteen Italian artists including AB himself: different combinations of symbols were associated with each name. The offset print was posted like a letter. Various farfetched interpretations have been put forward, but its meaning has never really been explained.

1968

This was a year of socio-political ideological upheavals and conflicts, above all in Turin, an industrial city.

“People from outside Turin used to come and see for themselves what was going on… But essentially I never joined in a procession. Perhaps I didn’t even agree with it much, I wanted to think of my own things, which held all my attention.”

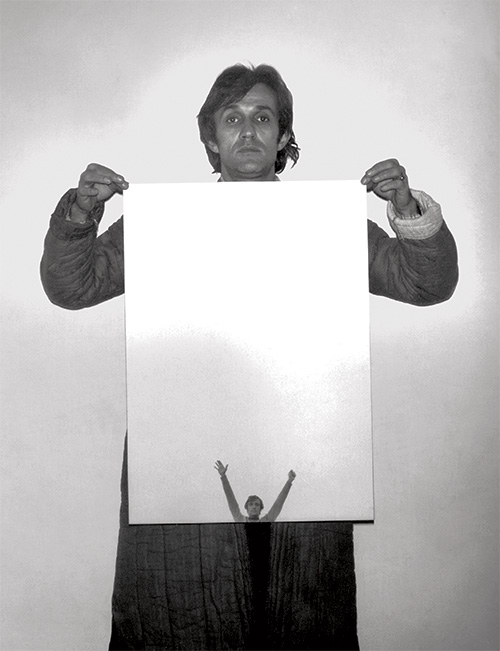

This year AB produced the “sculpture” Autoritratto negativo, the photo montage Shaman-Showman and finally a second montage Gemelli, which he sent to about fifty of his friends. From this double image he derived, in 1971, his new signature “Alighiero e Boetti.” On 7 February, he had his second solo exhibition at the Galleria Stein. The opening was recorded in a short documentary by Ugo Nespolo titled Boettiinbiancoenero. The film includes the work Pack, today lost, which was memorable because of his subsequent developments of the theme.

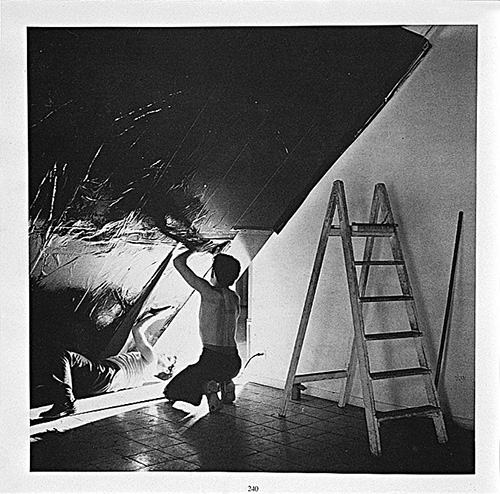

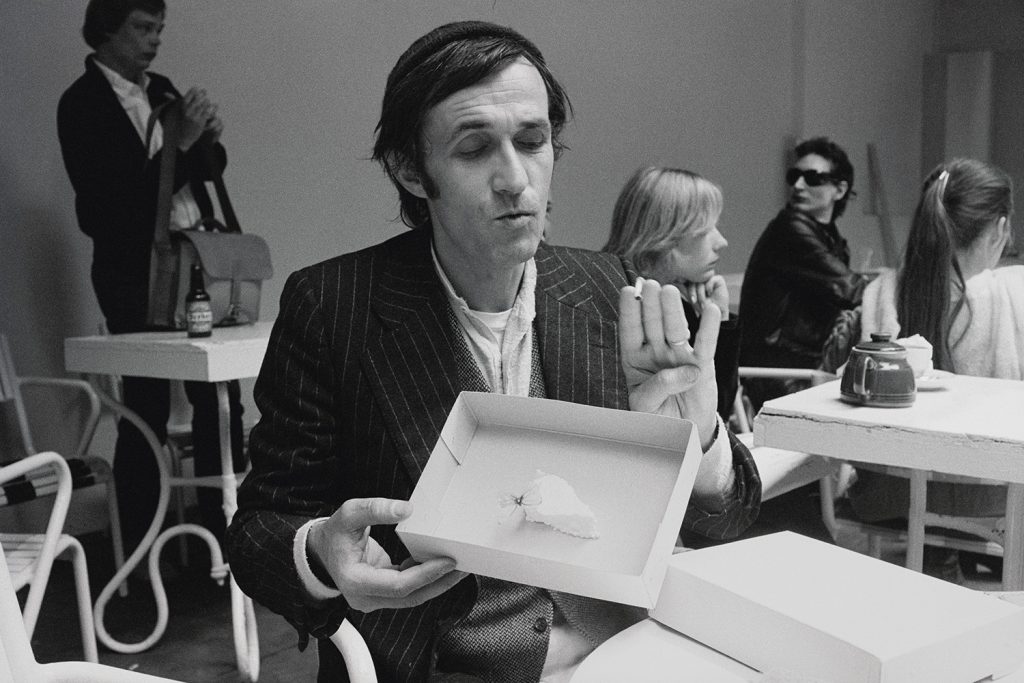

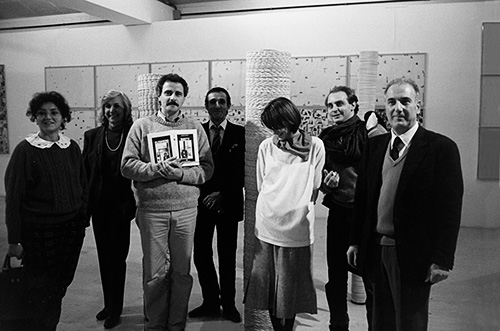

“Teatro delle mostre” Roma, 1968 – Courtesy Archivio Alighiero Boetti

In early spring Boetti took part in various group exhibitions including “Arte Povera” curated by G. Celant at the Galleria de’ Foscherari in Bologna. He exhibited Panettone and produced the poster Città di Torino: a plan of the city in which the streets are indicated with the colored names of the artists resident in them, including himself. The map was included with the exhibition catalog and distributed to the public.

AB also took part in two important group exhibitions in Rome, “Il percorso” and “Teatro delle mostre.”Both consisted of sequences of performances.

“Il percorso” was organized by Mara Coccia, director of the Galleria l’Arco d’Alibert. She invited the Turin-based artists Anselmo, Boetti, Merz, Mondino, Nespolo, Paolini, Piacentino, Pistoletto and Zorio to perform a sequence of events. “At the private viewing there were the artists but no works, because they were created before the eyes of the public on the three days of the happening.”

Boetti built three Colonne in the gallery, using thousands of scalloped paper napkins which he got from a cake shop, strung on three iron rods. The work was documented in a photographic record by Mario Cresci.

“That same day an exhibition of Pino Pascali’s was opening at the Attico. He was showing his Silkworms. Pino and I were really doing the same thing, in fact we were amazed. When I went out to buy the paper napkins at the cake shop, he went round to the drugstore for the colored brushes that he arranged next to each other. We had reached the limits of a certain potential…”.

The “Teatro delle mostre,” curated by Maurizio Calvesi, was held at the Galleria La Tartaruga run by Plinio de Martiis. He recalled the event: “The gallery was transformed into a laboratory… It looked like a stage or a film set.” The exhibition, originally subtitled “An exhibition every day – from 4 to 8 p.m.,” consisted of a series of performances with the direct involvement of the public. AB presented Un cielo: “Boetti … assembled a big frame covered with dark blue paper and the public were given the nails. Behind the frame there were spotlights. The nails were used to pierce the dark blue surface … and everyone produced his own constellation.”

Alighiero Boetti in Amalfi for “Arte Povera più povere actions”, 1968, Courtesy Lia Rumma

Plinio de Martiis, working in his own special tradition, asked the artists to produce a sign for the performances. At this time in Turin the “Deposit of Art of the Present” was set up. Some photos in the archives show displays of works by AB: Panettone, Legnetti colorati, a castiron work Boetti set on the wall and some plexiglas Cubi filled with various materials.

On 23 April, at Franco Toselli’s Galleria De Neuburg in Milan, Boetti had a solo exhibition with a presentation by T. Trini. The title of the exhibition, “Shaman-Showman,” corresponded to a photomontage which was enlarged as the exhibition poster and displayed in the streets (there also exists a smaller silkscreen edition). Boetti later commented:

“Showman and shaman, because you are always a wizard when you work with head and hand… And showman because every so often you have to be one!”

Conspicuous on the floor, transformed into a dry stream bed, were Colonne, Un metro cubo, Panettone, Legnetti colorati (initially titled Aiuola / “Flower bed”), a Pack galleggiante (an ephemeral work, like the general installation) and, concealed, Ritratto in negativo.

If this exhibition at the Toselli gallery represented the peak of the artist’s involvement in Arte Povera, the autumn exhibition in Amalfi, “Arte Povera più azioni povere,” organized by Marcello Rumma and curated by Germano Celant, marked its most extreme form. Boetti’s participation was described by Gilardi in these terms: “At the Arsenal, Boetti had accumulated and spread out in front of the entrance about thirty gadgets and samples of materials which, all labeled by his gallery, were on a square of white fabric placed on the ground.” The exhibition marked a radical breakthrough as he turned away from Arte Povera:

“With Shaman-Showman I quit. Then I did the work on squared paper using a tracing pencil… By the Amalfi exhibition I was really fed up with it all.”

In fact the Amalfi installation included some strongly conceptual works.

“There were three blue panels with three Dates, which I had requested from three women, referring to a future which interested them. They included Anne Marie… I had some idea of the energy a date can convey.”

Of the three dates, only one refers to the past, the others represent expectations, a rendezvous with the future.

“Dates? You know why they’re very important? Because, for example, if you write ‘1970’ on a wall it seems like nothing, but in thirty years’ time… Every day that passes this date becomes more interesting, it’s time at work…”.

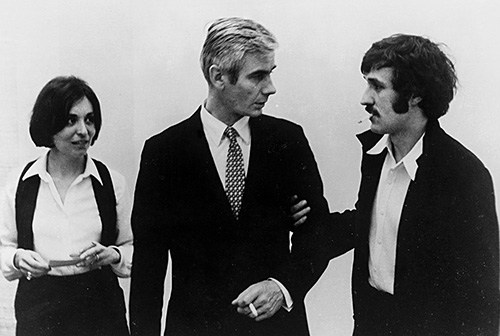

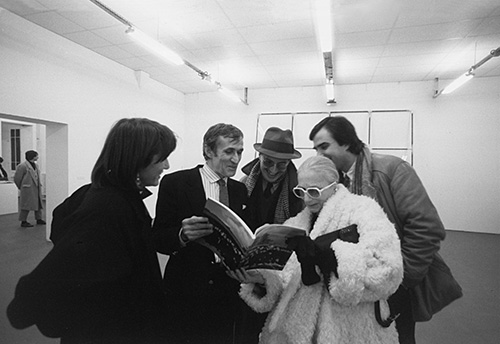

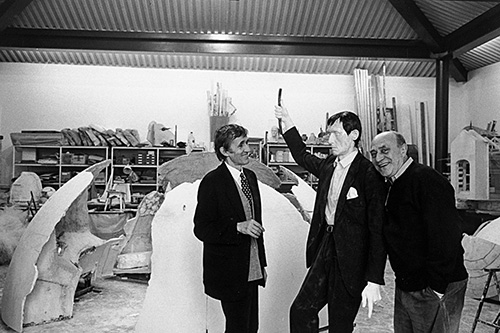

Alighiero and Annemarie Boetti and Enrico Castellani at the inauguration of “Shaman/Showman”, photo by Enrico Cattaneo

“Time at work”: in ’68 AB made a wooden panel with 1978 written on it and subtitled “art in ten years’ time.” The following year he carved on a wooden diptych a “continuing tombstone”: the centenary of his birth and the supposed date of his death.

Time and writing: again in ’68 AB performed a number of “poor actions” that consisted in writing in quick-setting concrete verses taken from Herodotus (Verso sud l’ultimo dei paesi abitati è l’Arabia / “To the south the last of the inhabited countries is Arabia”), from Marcuse (Per un uomo alienato / “For an alienated man”), from Rimbaud (J’ai embrassé l’aube d’été). The swift time of writing against the time of matter. Strangely enough all these works were only made public and exhibited twenty years later.

1969

22 March, Berne: the opening of “Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form,” curated by Harald Szeemann. The groundbreaking exhibition compared new trends in America and Europe by looking at Conceptual Art, Land Art and Arte Povera. AB exhibited Alighiero prende il sole a Torino il 24-2-1969, Tavelle, Luna (lost work). In the catalog, on the pages placed at his disposal, he added photographs of other works (also now lost), Sole meunière, Tritella, and a double photographic self-portrait: himself lying on the floor of his studio next to the Portrait in Negative made out of stones.

On 19 April, at the first solo exhibition in the Galleria Sperone, AB presented three works in mixed media: Io prendo il sole a Torino il 24-2-1969 (its second title, later definitively modified to Io che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969), Portrait of Walter de Maria, Vetrata (which reduced in size became Niente da vedere niente da nascondere). The invitation on paper reproduced the photograph San Bernardino, a portrait of Boetti with one hand open and one closed.

In May, again at the Galleria Sperone: AB took part in the group exhibitions “Disegni e progetti” with Territori occupati, a work embroidered on which returned to the first of the geo-political “forms” begun in 1967. The embroidery was sewn by Annemarie Sauzeau.

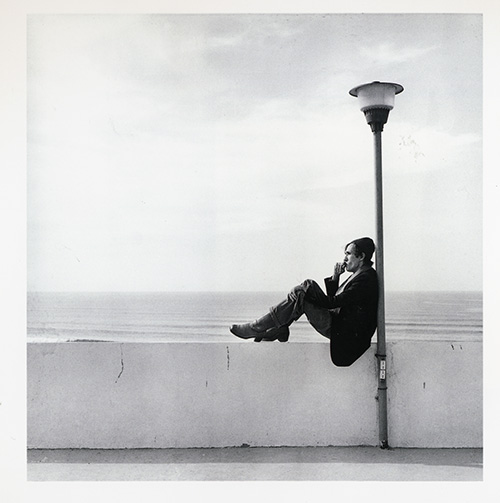

Alighiero Boetti near his self-portrait in negative, 1969

“In spring I left the studio I had in Turin, which had become a storehouse of materials, Eternit, pieces of concrete, stones… I left it all just as it was. I took the squared paper. The Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione consists of redrawing the squares.”

AB began a new series of works. The first example of Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione was also called 42 ore and was supplemented by a recording of the silence and soft noises during the time it took to make. It was exhibited in late September at the “Prospect 69” exhibition at the Stadtische Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf.

The title of this type of drawing refers to Vivaldi’s Opus no. 8, containing the twelve concertos which include the Four Seasons, and a type of music played by AB himself. “In the period Alighiero played a lot of music, he played tabla drums, practicing with compositions based on the proliferation of numbers as musical rhythms. He interpreted ‘Cimento’ (‘contest’) as meaning this type of exercise, how to do musical scales, which was also a ‘contest’ on paper.”

15 July, Turin: his first child, Matteo, was born.

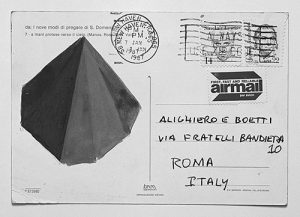

In summer AB began a work in progress, the Viaggi postali. He created twenty-five virtual routes for twenty-five “travelers,” who were friends, collectors and artists, including Marcel Duchamp (who had recently died), Bruce Nauman (whom he met at the exhibition “Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form”), his friend Paolini, the critic Argan and his newborn son Matteo. The work consisted in imagining the addressees had traveled to various places, 181 in all, and then sending them letters they would not receive, since they were obviously not resident at the addresses chosen.

The letters that returned undelivered to the sender, AB, would be put in ever larger envelopes and forwarded to the other points on their journey (the first envelope contained the complete itinerary). The result was twofold. On the one hand the twenty-five final envelopes containing all the preceding ones constituted a single work, called Viaggi postali (“Postal journeys”). On the other the xeroxed copies of recto and verso of the envelopes, made each time before posting the letters again, testified to the 181 stages and constituted the Dossier postale, creating an edition of 99 copies of no fewer than 36,000 photocopies, curated by AB and Clino Trini Castelli.

The Dossier postale recounts the twenty-five imaginary journeys enclosed in the final parcels. The numbering of each example appears, again on file number 181, in a stamp, devised by Clino Trini Castelli, which refers to “file 104,” meaning the last stage of the journey by Bruce Nauman.

“It’s one of the finest works I’ve ever done. Really complicated, it lasted a year.”

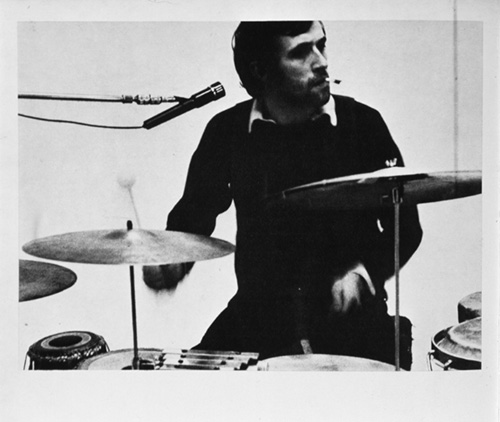

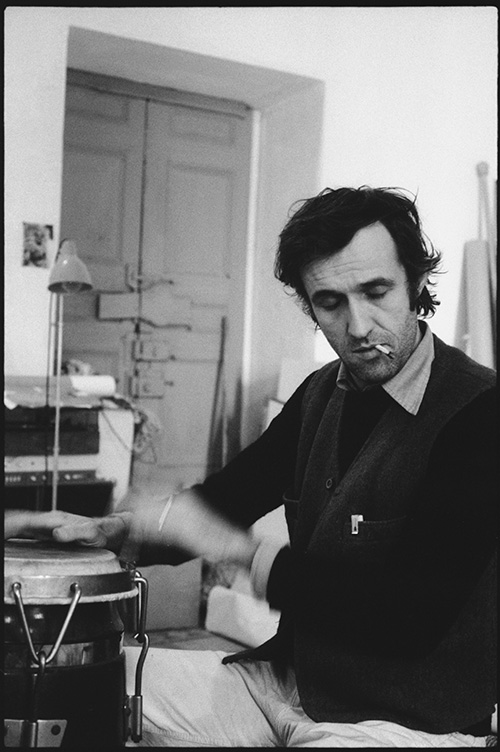

Alighiero Boetti on his drums in the Sperone gallery, 1969, photo by Paolo Mussat Sartor

In autumn he took part in various group exhibitions, lavishing particular care on the catalogs, which at the time were considered by artists as works in themselves, self-sufficient art projects. He worked on the xerox “portraits” Autoritratto and Ritratto di Annemarie, consisting respectively of twelve and nine photocopied sheets, which all show the artist’s face intent on communicating in deaf-mute alphabet. He also turned his hand to other experiments, again using a photocopier, for example by letting some chicks wander about on the surface of the photocopy panel.

“I’d go round to the Rank Xerox showroom and pay my hundred liras a copy…”.

On an old map printed in black and white, AB colored in the various countries using the colors of their flags. This Planisfero politico (in two variants) was the starting point, developed in 1971, for his later embroidered maps. At the same time he planned to have a globe made, of sizable dimensions, which would show only the contours of the land and sea beds, without the presence of water. The outlines of the continents would not be perceptible, so the effect would be like the surface of the moon. It was never made because it proved impossible to obtain accurate scientific data about the features of the seabed, which was classified information during the cold war. There survive two small plaster reliefs, fragmentary models of the initial project.

1970

Boetti completed the series of Viaggi postali over the course of the year. Part of Dossier postale had already been presented in Bologna at the “Terza Biennale Internazionale della giovane pittura” in January. Boetti began his first works based on permutations and combinations of stamps. His first Lavoro postale, based on three different stamps (with six possible combinations, hence six envelopes), was sent to the Galleria Sperone.

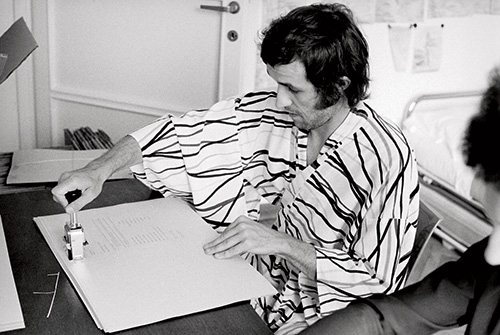

Alighiero Boetti during the Dossier, Milan 1970. Photo Giorgio Colombo

In Munich that April, during the survey “Aktionsraum 1,” Boetti carried out a sequence of actions which included giving a lecture in two languages, Esperanto and Italian, followed by the gradual tearing up of a sheet of paper on the principle of Raddoppiare dimezzando (doubling by halving); then, finally, for the first time, he did two-handed mural writing, simultaneously towards right and left, using the text puntopuntinozerogocciagerme.

Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (varied across numerous sheets of paper) and Millenovecentosettanta (EMEIELLE … the spelling of the year 1970) were his most innovative works. They were presented at all his solo or group exhibitions in Europe and defined the birth of conceptual art.

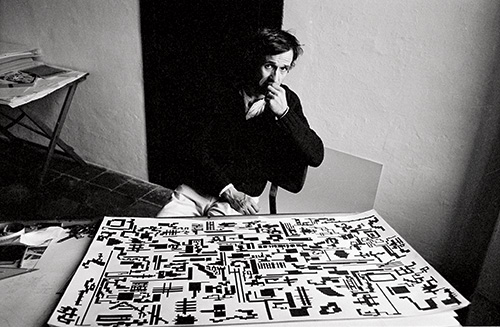

Alighiero Boetti in front of the Manifesto at the Franco Toselli gallery in Milan 1970, photo by Paolo Mussat Sartor

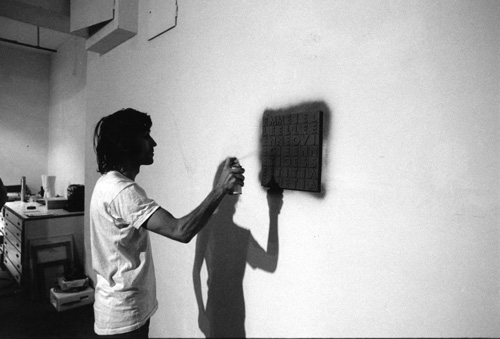

Of Millenovecentosettanta, a square of forty-nine letters, exists a version in lace and others made of wood or cast iron. AB sprayed green paint over the latter for every installation and the halo that spread beyond the limits of the square united the iron and the wall in a single “cloud.” This arrangement of a date as a square was the source of all his language squares in subsequent years.

In “Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, Land Art,” an international exhibition curated by G. Celant at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna in Turin, AB exhibited a castiron version of Millenovecentosettanta. It was also the image printed on the exhibition posters. Among the other conceptual exhibitions, a major event was “Processi di pensiero visualizzati” at the Kunstmuseum in Lucerne, curated by J.C. Ammann. In the pages placed at AB’s disposal in the catalog, he presented four spare drawings linked to four poetic quotations from Johnson, Yeats, Roheim and Hopkins.

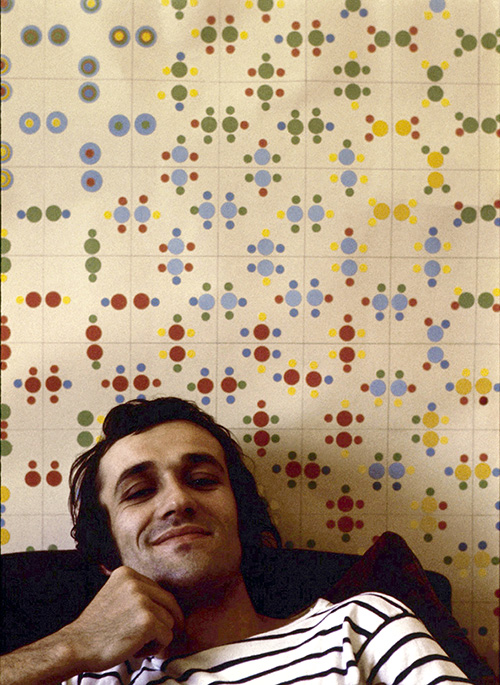

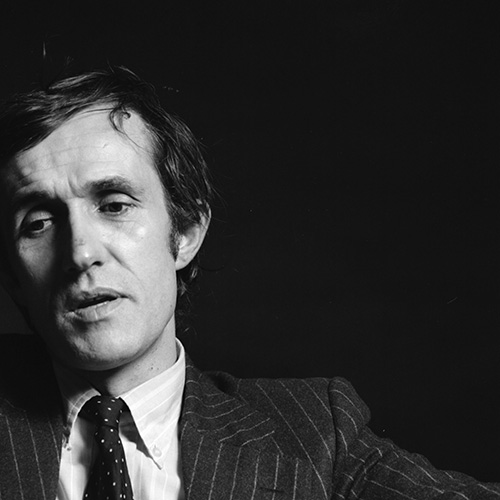

Alighiero Boetti, 1970, photo by Paolo Mussat Sartor

He continued to experiment with squared paper. After the tracings and word squares, in 1970 he adopted a new approach: using plain sheets of copybook paper, he began writing with commas, a system he developed further in 1972 in his works in ballpoint pen.

All through the summer he withdrew, “encamped” in Franco Toselli’s Milan gallery, “closed for the holidays.” He took to its extreme development the interplay of mirrored combinatorial marks on a checked surface, which he had begun in 1967 on a wooden checker board and continued with colored marks on sheets of drawing paper. In this way he created Estate 70 (“Summer 70”), a roll twenty meters long, covered with thousands of self-adhesive stickers. He again adopted the same colored mechanism in a project using bathroom tiles, but never completed it.

AB while spraying Millenovecentosettanta, 1970, photo by Giorgio Colombo

At the end of the summer, in his passion for serial works, AB planned to place geographical features in progressive (decreasing) order, with a classification of the rivers of the world which went well beyond the modest lists found in encyclopedias. His wife was involved in the project. In October Annemarie Sauzeau started to draw up a list of the world’s one thousand longest rivers. She made preliminary contacts for publication with the Istituto De Agostini in Novara and the Geopaedia project at Pergamon Press in London, and acquired complex unpublished scientific data through correspondence with geographic institutes and university departments in Africa, Latin America and Asia. The long project was brought to completion in 1974 with the final classification, while it took another three years for the publication of Classifying, the thousand longest rivers in the world, a volume of over a thousand pages. The idea behind the project was clear from the start:

“It’s a linguistic work which grew out of the idea of classifications. It’s based on measurements. Geography has nothing to do with it.”

Alighiero Boetti at the inauguration of the exhibition of Mel Bochner – Galleria Toselli of Milan, 1970, photo by Giorgio Colombo

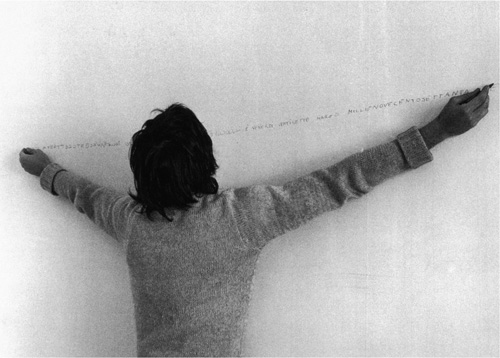

AB’s conceptual position emerged clearly throughout 1970. For example, in autumn at the Kunstverein in Hanover, AB participated with a performance in the video survey identifications, organized by Gerry Schum. In it he stood with his back to the camera and wrote on the wall with both hands simultaneously the sentence: Giovedì venti quattro settembre mille nove cento settanta (“Thursday the twenty- fourth of September one thousand nine hundred and seventy”). Already in March, Paolo Mussat Sartor photographed Alighiero Boetti in his house on Via Luisa del Carretto writing the date on the wall with both hands Oggivenerdiventisettemarzomillenovecentosettantaore.

In Rome the year closed with his participation in an important group exhibition: “Vitalità del negativo 1960–70,” curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, organized by the Incontri Internazionali d’Arte at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. Boetti exhibited a series of sheets from Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione.

AB two-handed writes 1970, photo by Paolo Mussat Sartor

1971

With the addition of the newly founded state of Bangladesh in March 1971, he completed a work in progress begun in 1967, a collection of geopolitical maps. The final work, titled Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967, made on copper plates, engraved after the model of his tracings on paper, was exhibited at the Galleria Sperone in summer. In autumn an edition printed on paper was issued.

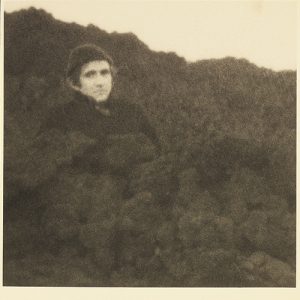

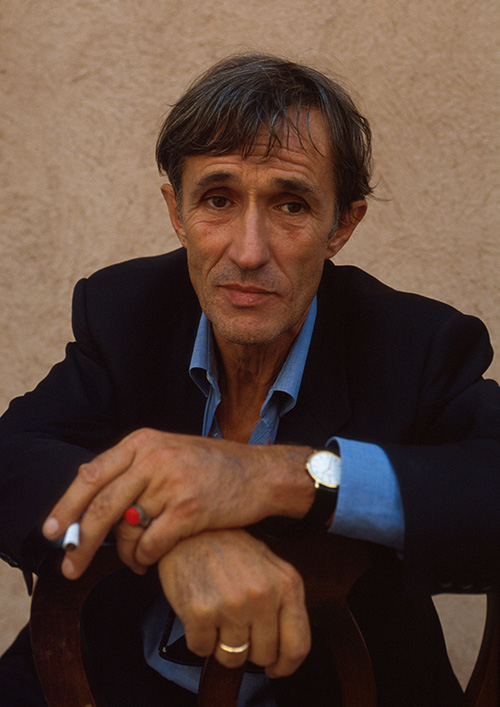

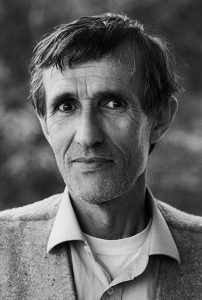

Portrait of Giovan Battista Boetti, 1743-1794

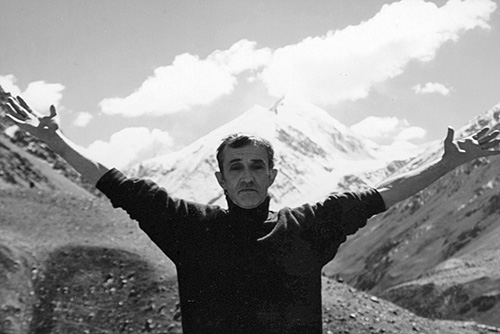

Meanwhile, in late March AB left for Afghanistan and stayed there several weeks. This was the beginning of a ritual of making two visits every year which continued up until 1979. He chose Afghanistan for various convergent reasons. One was that an ancestor of his, the Dominican friar Giovanni Battista Boetti (born in Monferrato at Piazzano in 1743) had been sent to Mosul at the head of the Evangelical Mission for Asia Minor. Subsequently he converted to Sufism, Persian Islamic esotericism, and was considered an apostate by the Roman Church. Calling himself the Prophet Mansur he became one of the heroes of the resistance against Tsarist imperialism in the Caucasus, with risings from Armenia to Chechnya. Two centuries later there appear extraordinary parallels between the two Boetti, both in the splitting of their identities and their geopolitical interests.

Two months before setting off for Afghanistan, AB duplicated the sole existing portrait of Giovanni Battista Boetti as a young Dominican friar and added it to the catalog of the group exhibition “Formulation” (Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover), next to another “indirect self-portrait”: his own profile in a very Pop version in a wooden silhouette, painted in 1970 by the Turin-based painter Pietro Gallina, which the artist loved to present in exhibitions among his own works. AB gave other possible reasons for going to Afghanistan:

“My interest in distant things wasn’t strong when I became an artist. I thought of travel in strictly personal and hedonistic terms. The principal factor in its allure was very precise: I was fascinated by the desert, and not just the natural desert. In an Afghan house for example, there’s nothing: not a single piece of furniture, hence none of the objects that are usually placed on furniture… What attracted me most was the blankness, the civilization of the desert. Afghanistan is a country of mountains, where villages are built on mountainsides so as not to waste the fertile land in the valleys. Nothing is added to the landscape. They clear the stones and use them to build their cube-shaped houses, as in Paul Klee’s watercolors, and they lop the branches off a tree to make the loadbearing structure.”

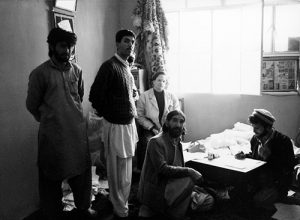

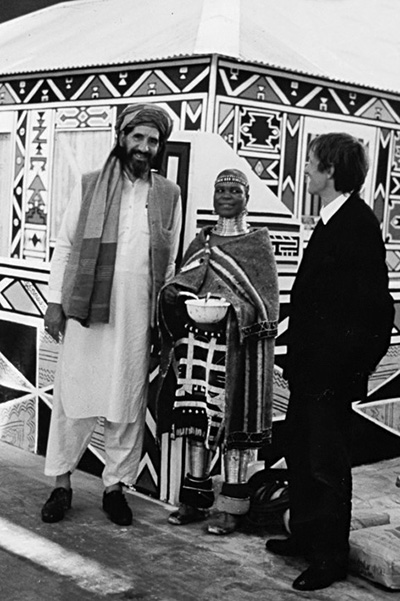

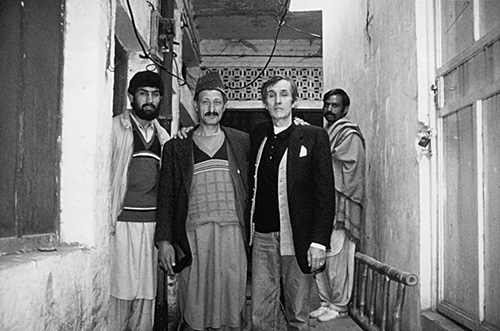

One Hotel in Kabul, courtesy Archivio Alighiero Boetti

In Kabul he had two squares of fabric embroidered with two dates, 11 luglio 2023 – 16 dicembre 2040, based on the diptych made previously in two versions, one of lacquered wood and the other brass.

This was the first of the embroideries he commissioned from Afghan women. On returning to Italy, in May he exhibited the diptych in the brass version at “Arte Povera – 13 artisti italiani,” a group exhibition held at the Munich Kunstverein. For the catalog AB asked (in vain) for the four pages at his disposal to be replaced by a single white sheet of industrial paper, of the equivalent weight, with nothing but his name printed on it.

Meanwhile, on 4 May, by sending the first telegram (“2 days ago it was 2 May 1971”) he began an essential work: the sequence of telegrams that was to form the Serie di merli disposti a intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muraglia (“Series of battlements arranged at regular intervals along the ramparts of a wall”). It is based on the rule of doubling the time intervals after the initial date (2, 4, 8, 16…). AB immediately designed a special display case to contain the greatest number of telegrams that could be sent in his lifetime. The fourteenth and last one would be sent by the artist in 2017, when he would be seventy-seven years old. The space for the last of the “battlements” was left empty in the “wall.”

At the end of summer, in the exhibition curated by Achille Bonito Oliva for the International Theater Fes- tival in Belgrade, Boetti repeated his two-handed mural writing performance.

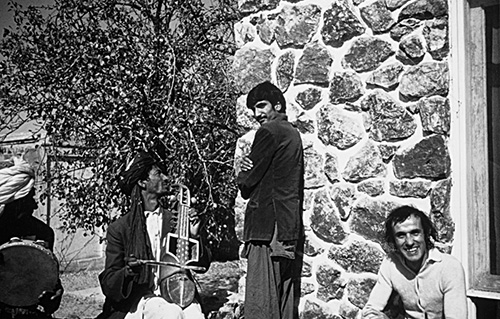

Alighiero Boetti with musicians at One Hotel in Kabul in 1971, courtesy of Alighiero Boetti Archive

In September AB returned to Kabul, taking some pieces of linen, on which he had impressed a map of the world by photographic projection, colored according to the national flags (like the Planisfero politico, his earlier work on paper dating from 1969). The young ladies at the Royal School of Needlework took a whole year to complete the large Mappa and six months for the smaller ones.

At the same time further maps were commissioned from a family in the village of Istalif. The preliminary work for the embroidery was always done in Italy.

Every minor detail was specified: the forms of the continents and the boundaries of states, the forms and colors of the flags, the changes over the years to national boundaries and flags to reflect political changes—even variations in the rules of the projection of the earth’s curvature. In the early years the date registered on the embroidered selvage marked the completion of the embroidery in Kabul. After ’79 the date was generally inserted in Rome together with the mapping, so it marked the beginning.

The postal works with Italian stamps were followed by the first with stamps from Afghanistan.

During his stay in the country he created One Hotel, in a small mansion house with a garden in the Sharanaw residential quarter of Kabul. Its address was Zarghouna Maidan. An initiative of this kind was fairly simple under the monarchy of Zahir Shah. Its management was entrusted to the young Gholam Dastaghir, who had some [experience in the business. The hotel shared the fate of the country. It had to close a few years later, long before the official Soviet occupation.

Returning from Afghanistan, on 24 September AB exhibited at the Italian section of the Biennale de Paris, curated by A. Bonito Oliva. At its close, the same works (Viaggi postali, Dossier postale and Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967) were exhibited in Rome at the Incontri Internazionali dell’Arte, in the group section titled “Informazioni sulla presenza italiana.”

The 99 Postal Dossiers completed in Milan in 1971, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In the same period AB began to produce works written in blue ballpoint pen on white cardboard which played on his name and identity: AB, ALIGHIERO BOETTI MADE IN ITALY, ABEEGHIIILOORTT, AELLEIGIACCAIEERREOBIOETITII. Then finally he began to split his identity in two by inserting “and” in his name, hence writing it “Alighiero e Boetti.” In this way he expressed the equivocation created by the photo of his twin selves in ’68. Various statements he made show that the decision was a true conceptual operation:

“I always worked on the half and the double, and the missing unity—something that never exists. I used this mechanism in various works, including one like my first name and surname by putting ‘and’ between them… They become two people, and not just linguistically but really, because some people actually think I have a twin—and it’s true.”

Boetti created the language square Ordine e disordine on paper in 1971. Its material composition differed from the square titled 1970, sprayed with paint on paper. It was created as a negative, the color being sprayed over the surface but was covered by a template bearing the lettering. Apart from the formal composition of sixteen letters, the concept conveyed by the two words was of fundamental importance in the artist’s thought:

“I worked a lot on the concept of order and disorder, disordering order or ordering certain kinds of disorder, or presenting a visual disorder that was actually a representation of mental order. I think everything contains its opposite, we always have to seek one in the other: order in disorder, the natural in the artificial, shadow in light and vice versa.”

1972

In February Boetti had a solo exhibition at Franco Toselli’s gallery in Milan, “Franco Toselli c/o Alighiero Boetti.” Some postal works were exhibited, notably Centoventi lettere, presenting 120 stamped envelopes based on the number of permutations possible starting from five, in this case five Italian stamps of different values and colors. This was the first postal work in which the envelopes contained “messages” to be exhibited outside the envelopes: 120 sheets of tissue paper, each with a puzzle-drawing (Pack) in black ink. The drawings removed from the envelopes were bound in a volume with a red cloth cover.

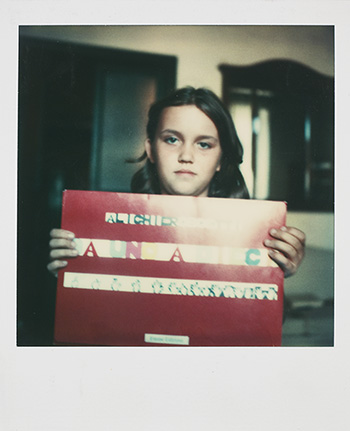

On 16 March Agata, his second child, was born.

After spending spring in Kabul, AB brought back to Italy the first medium-sized embroidered Mappe (of the two larger Mappe, one was completed the following autumn, the other only in spring 1973).

“The first reactions were terrible. People were annoyed. It should be said that few artists at the time had their pieces made by craftsmen. The public of the day found it both embarrassing conceptually and too ‘pretty.’ But all the collectors wanted one!… I come from Turin, I’m a northerner, and in those days I was a lot more rigorous, far too rigorous. To the point where I never used color in my work. Living in Rome did me good. I then opted for openness, generosity, and freed myself from that excessively rigorous idea that you should only make a single work out of a single idea. It was Gian Enzo Sperone who finally convinced me… From then on I took the opposite approach, profusion. I turned to serial art.”

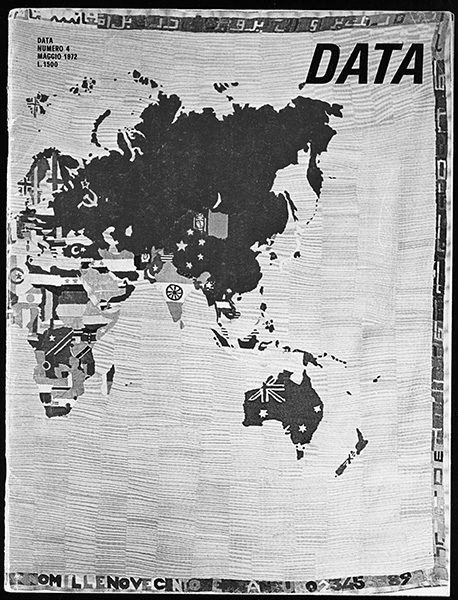

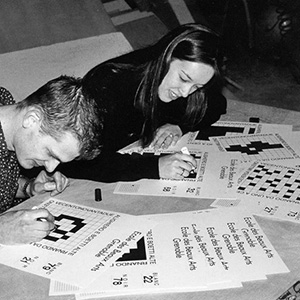

The May issue of Data magazine carried a detail from a Mappa on its cover. The same issue had an article by Tommaso Trini titled “Abeeghiiilooortt.”

The journal Data, May 1972

18–30 June, “Alighiero e Boetti,” solo exhibition at the Galerie MTL in Brussels. This was the first time Boet- ti’s name was given this form.

In summer AB presented his work at four important group exhibitions held at close intervals. On 29 April, “De Europa” (a group exhibition of thirteen Euro- pean artists) at the John Weber Gallery in New York exhibited Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967. On 11 June, at the 36th Venice Biennale, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, Boetti again did his two-handed writing performance.

On 23 June, at the Festival of the Two Worlds in Spoleto, in the exhibition “420 West Broadway at Spoleto Festival,” he exhibited the sequence of Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967. Finally, on 30 June at the fifth edition of the Kassel Documenta, curated by H. Szeeman, he presented a highly complex Lavoro postale, the first made by starting from six (Italian) stamps of different values and colors. The number of possible permutations enabled the artist to present 120 envelopes, stamped and obliterated, addressed to the Galleria Sperone. In the same period he actually undertook the permutations of seven (Italian) stamps, giving 5,040 possible combinations, hence 5,040 envelopes addressed to himself as Victoria Boogie-Woogie.

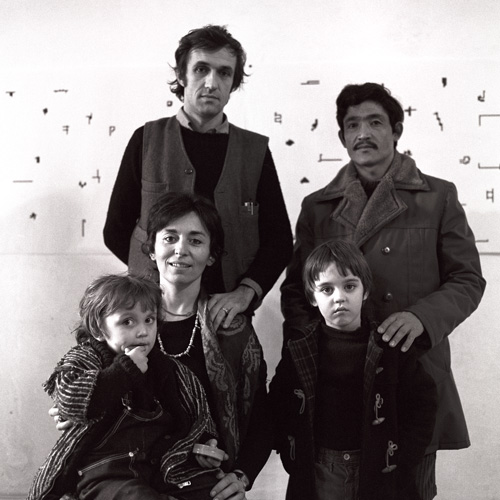

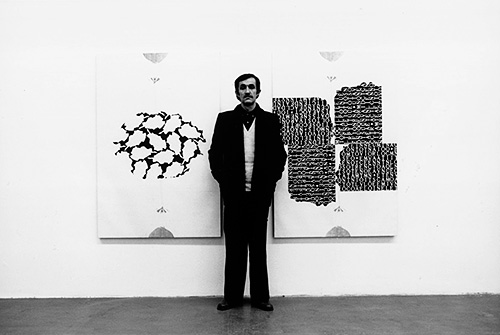

Order and disorder, Kabul 1972, photo by Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti. Courtesy Agata Boetti

In Kabul in September Boetti arranged for the embroidering of a first small word square, Ordine e disordine, measuring about 20 × 20 cm, embroidered in many colors. He also started another type of embroidery whose title, I Vedenti (“The Sighted”) refers to the central lettering, which is interwoven with the colorful ground and so barely perceptible.

In October, returning to Italy, he joined his wife and children at their new home at 38 Via del Moro in Trastevere, Rome.

He began the cycle of ballpoint works done “in negative” (with the blank “reserve” emerging against a ground hatched in ballpoint). He again wrote his name in different ways, both by using the letters of which it was composed and by playing with the letters of the alphabet and commas. The structure of all of his works in biro “written” in white commas meant that each comma was given the value of a letter, being deciphered on the basis of Cartesian axes: one variable consisted of reading from left to right and the other of the letters of the alphabet.

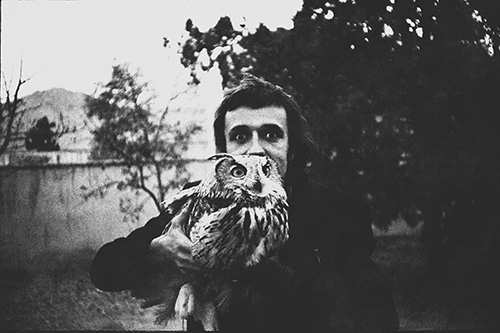

Alighiero Boetti and the owl Rémè in Kabul in 1972, Courtesy of Alighiero Boetti Archive

He wrote AEB, ALIGHIERO, AIIEOOEI/LGHRBTT (separating vowels from consonants). Finally in ’73 there appeared Ononimo, the supreme variant of his identity, a neologism fusing the Italian words for “homonym” and “anonymous.” It was presented in sequences of eleven inseparable sheets (11 being his favorite number) in blue or red, while other versions of Ononimo are single or “isolated” (with AB writing “isolato” next to his signature). The background, hatched in with ballpoint, was a long, laborious work and was delegated to other hands, precisely because the anonymity and variety of the “hand” were part of the project, though with a trace of irony the artist suggested other reasons:

“I often get other people to do the work, even though I’d really like to do it myself. I’d love to be able to go out in the countryside with a sheet of blank paper and take six months filling it in. I’d like to but I can’t. I just can’t do it, after two minutes I’d go crazy. But since I like the thing in itself, I find some people to do it, rather like in Muslim countries, where if you can’t go to Mecca you pay someone who goes for you and says your prayers, he does it all for you…”.

The first person he asked to do the work was a friend in Turin, Gigliola Re. When Boetti moved to Rome, she immediately found him another collaborator there.

Number 62 of Bulletin, a magazine published by the Art & Project Gallery in Amsterdam, was devoted to Boetti. It had a black and white two-page spread illustrating one of his postal works: six envelopes from Afghanistan addressed to himself in Turin.

1973

On 20 January, the group exhibition “Eight Italians,” organized by Sperone, opened at Art & Project in Amsterdam and MTL in Brussels. Boetti exhibited with De Dominicis, Merz and Zorio (the other subgroup comprised Anselmo, Paolini, Penone and Salvo). Besides a postal work, AB exhibited two of his first works drawn in negative in ballpoint, ABEEGHIIILOORT and ALIGHIERO E BOETTI, a “sculpture” from 1971 made up of three elements in silver titled Tre and a calligraphy Millenovecentosettantadue.

In February, at the Galleria Marilena Bonomo in Bari, he had a solo exhibition “Alighiero e Boetti. Il progressivo svanire della consuetudine.” AB exhibited the postal work Quadratura del dieci (1972). This was a “self-arrangement” of sixteen envelopes, and some of the new works in ballpoint, particularly the one that gave the title to the exhibition.

In March AB had his first solo exhibition at the John Weber Gallery in New York. On display were a Mappa and two Lavori postali, including Victoria Boogie-Woogie. Apart from a review by Bruce Boice in Art- forum, the exhibition failed to attract much interest. Soon after the New York inauguration, Boetti left for Kabul. He returned to Italy in the company of a young Afghan, Salman Ali, who lived with him and his family until the artist’s death.

Alighiero Boetti and Salman Ali in the study of Piazza S. Apollonia 3, 1975, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In spring he moved from his home at Vicolo del Moro 38 for the nearby Piazza Sant’Apollonia, where, besides an apartment, he had a large studio. The windows gave onto Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere and looked towards the Romanesque church.

In May, in a solo exhibition at the Galleria Sperone-Fisher in Rome, Boetti presented four important works: one Mappa, the Serie di merli disposti ad intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muraglia was shown for the first time and two large works in blue ballpoint: Il progressivo svanire della consuetudine and the dip- tych Mettere al mondo il mondo.

In the same month, at the 10th Quadriennale Nazionale d’Arte in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni he presented two works from his Arte Povera period, Lampada Annuale and Manifesto, together with a recent Lavoro postale of 492 envelopes.

On 7 June, with a solo exhibition at the Galleria Toselli, he confirmed a characteristic already perceptible in his solo show of the previous months: his postal works, ballpoints and embroidered maps were by this time parallel typologies enriched by overlaps and affinities. The manual phases of this highly diversified work was partly delegated to others—the embroidery in Afghanistan and ballpoints in Rome—while the artist personally dealt with all phases of the postal works, notable for the use of the different kinds of stamps available in the various countries where he stayed. The Serie di merli disposti ad intervalli regolari lungo gli spalti di una muraglia was again exhibited, and Giorgio Colombo took a photo of the work in progress.

Alighiero Boetti prepared in 1978 at the Kunsthalle in Basel “720 letters from Afghanistan”, realized in 1973-1974, photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni

The ballpoint works were stepped up after the summer, when AB commissioned Mariangela De Gaetano not only to do the hatching in biro herself on a number of sheets (the various signs, letters of the alphabet, commas or words were always drawn by the artist himself) but also to organize and coordinate the work by others.

She recounted: “I chose people from all quarters of the town, of all ages, and they all worked in different ways. The only rule they had to follow was not to let the white appear between the hatching. For the rest, they could do the work as they wanted… Some people drew thicker lines, some people stiffer, others did the work more mechanically, lost in thought, daydreaming, a bit like automatic writing. Boetti often wouldn’t let me tell him who had done a sheet, he liked to guess. He recognized the line of a woman. Then he used to ask me about all of them, who they were and what they did in life. The work took a long time. Personally I took a year to complete the first one, a single sheet measuring a meter and a half out of more than 4 meters, Il progressivo svanire dalla consuetudine.”

The first ballpoints done in Turin were exclusively in dark blue ink, while in Rome he used black, red and green. In the first compositions the text can be discovered by relating commas and letters (reading vertically or horizontally). This is the case of Mettere al mondo il mondo (consisting of two or five elements), Immaginando tutto (two elements), I sei sensi (eleven elements), Il progressivo svanire della consuetudine. The same mechanism was applied to the “portraits” based on the names of friends and often consisting of whole families. Meanwhile he continued with the type of composition with words written in full at the top of the sheet, including ONONIMO, or dates written in words.

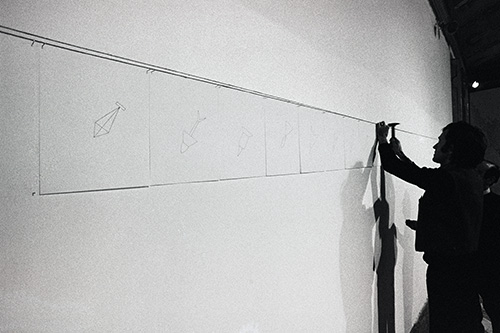

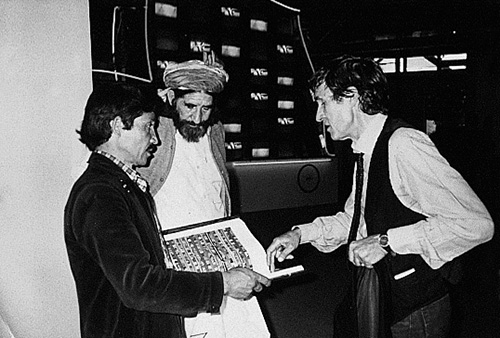

Alighiero Boetti realizes the portrait of Giorgio Colombo at the Franco Toselli gallery in Milan, 1973, photo by Giorgio Colombo

These inscriptions were chosen on various criteria: at times they were the titles of other kinds of works he did (Dare il tempo al tempo, Raddoppiare dimezzando). At times they were quotes, such as the mystical Sufi saying La notte dà luce alla notte (“The night gives light to the night”). The writing of these sentences in ballpoint, in a number of versions but all different in coloring and hatching, continued through the following years. In his Rome studio AB prepared the sheets for the ballpoints while his private research continued to be focused on squared paper, working on language squares and the transformation of sentences into “constellations” of commas.

In the periods spent in Kabul, he oversaw the work on the embroideries and at the same time at the One Hotel prepared his postal works, the drawings to be inserted in the envelopes and the permutations of stamps. The most challenging of the postal works produced in Afghanistan was definitely 720 lettere da Kabul. Prepared in autumn ’73, it consisted of 720 sheets prepared by AB, to be completed with a phrase in Farsi. Dastaghir was commissioned to write these phrases and then send them to Rome in the course of the long Afghan winter of ’73–’74.

“When the hotel business fell through because of the revolution and everything got eliminated, including hotels, my partner was there, with winter approaching, jobless and without a cent.

So I organized this colossal work and asked him to write a page a day during those months, putting down the events of his life, his childhood, memories, stories… I prepared it all, envelopes, stamps, a really long job. And then I gave him 720 sheets which I had stamped, using a rubber stamp I had made specially. It was the image of the number one thousand…”.

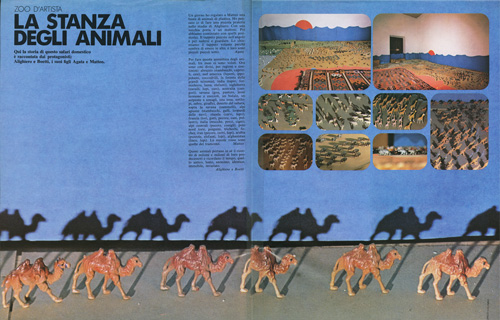

Besides the Mappe, in Afghanistan Boetti had the works Ordine e disordine embroidered, no longer as a single small tapestry but with a view to creating large composites made up of several pieces, all bearing the same phrase but in each case colored in different ways. (One composition was made up of forty-nine pieces and another of a hundred.) Other “small embroideries” followed in the years ahead.

“I drew about 150 sentences that could be arranged in squares… Today when I come across an expression like ‘la forza del centro’—a yoga precept—I know instinctively that the number of letters enables it to form a square.”

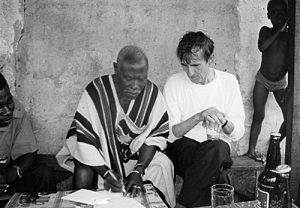

Alighiero Boetti looks at his Maps in the family in Todi, photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni, 1975

In late November “Contemporanea” opened in Rome, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva in the new car park at Villa Borghese. The works by Boetti on display were Ping Pong and Dodici forme dal 10 giugno 1967. Caroline Tisdall, in the London Arts Guardian, reviewed the exhibition as the “biggest ever mounted in Italy, with almost one hundred artists, a true challenge to Kassel.”

Of Boetti she wrote: “… Alighiero Boetti conveys the sense of the artist as a removed figure, somehow anonymous but observing and recording events in the ‘real world.’ One of his works on show is a series of etched copper plates: sections of maps. They are in fact the maps, one to a plate, of all the places in the world in which some political atrocity happened over a period of time a couple of years ago. So discreet is the use of material that the unmarked maps become shapes on a plate unless you know the circumstances in which they were done.” AB bought a house in the countryside not far from Todi in Umbria. It was to become his point of emotional and domestic stability, to compensate for the nomadic restlessness of his “twin” self.

1974

AB had already spent two years thinking about the need to create a portfolio that would bring together drawings and projects of past and present activities.

He involved the printer Rinaldo Rossi, who had already worked with him in ’67. When completed in ’76, with eighty-one plates, the portfolio was given the definitive title Insicuro noncurante. Perhaps while he was working on this, the artist realized that some works related to the drawings he was collecting had been lost. They were the works exhibited in his solo exhibition at the Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa in December 1967 and reproduced in the catalog. He therefore authorized in writing a friend of his, a Milanese art dealer, to remake “the works in concrete produced in 1967 which have been destroyed. Firstly: 100 quadrati and A coltello.” But these works were never remade and today only period photographs of them remain.

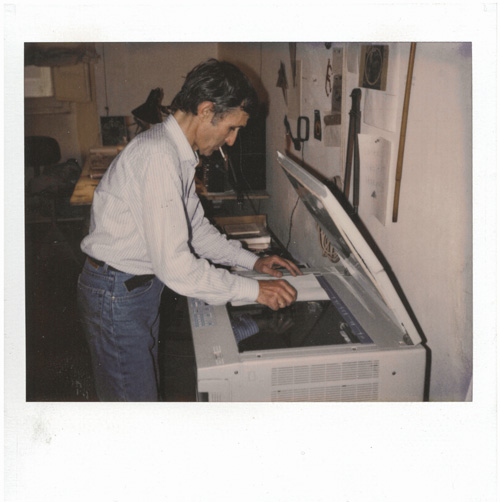

Alighiero Boetti in front of the Natural History of Multiplication in his studio in Trastevere, photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni

The spring issue of Data carried an article by Tommaso Trini titled Alighiero Boetti: The World’s 1000 Longest Rivers. The Boetti had almost completed the classification.

In April, Boetti traveled to Afghanistan with Francesco Clemente. In May at the Lucerne Kunstmuseum, AB participated in the group exhibition “Ein Werk für einen Raum” (each artist presented a single work in a room measuring 7 × 7 meters), curated by J.C. Ammann, where he showed the large Dama. In the catalog Ammann wrote: “Form does not mean formalization, an abstract plan of the work. Always starting from life, Boetti gives the work a richness of aspects whose formalizations, often lapidary, are the hallmark of the cosmos: Ordine e disordine arranged in a square is an example.”

The curator saw a continuity in Boetti’s work, through concepts like “the problem of harmony” or “the annulling of contradictions as a categorical intent.”

Alighiero Boetti and Francesco Clemente in Kabul in 1974. Courtesy of Alighiero Boetti Archive

In the summer he traveled widely in Guatemala. He returned with the series of photographs titled Guatemala, on the theme of the self and the other.

“Four photos, taken by four photographers who had come to the village festival, with their backdrops. Each photograph was printed in two copies, one being given to me, the other to my companion in the photo. Here in Italy, the foreigner in the photograph is the Guatemalan. Back there, in the photo posted on the wall of some house perched on one of the many volcanoes, I’m the foreigner.”

Alighiero Boetti in front of Estate’70 in his Roman studio, 1975, photo by Antonia Mulas

Following Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione, Boetti produced a new type of work. It was executed on sheets of squared paper measuring 70 × 100 cm. The procedure consisted in blackening some of the squares using ballpoint (as he had done in Autodisporsi, the invitation to the Galleria Verna) on the basis of various arithmetical mechanisms: quantitative equivalences between addition and subtraction, alternation between odd and even, the infinite potential of multiplication, and periodic numbers, always by starting from elementary rules capable of generating endless invention.

“Number is the sole real entity that exists in the universe. Numbers are the sole entities that exist independently, in the sense that, if is true that by convention we put B after A, it is not by convention that we put 2 after 1, it is an overwhelming reality. For example, when I see a piece of quartz, I cannot see it as something dead. I see it as a formula of numbers that at a certain moment—perhaps because a drop falls and triggers some chemical procedure—grows and in an instant this perfect, crystalline hexagon appears, these perfectly interlocking molecules… Fibonacci teaches that the number of seeds in a sunflower develops in a precise series. Numbers are crazy entities, totally crazy…”.

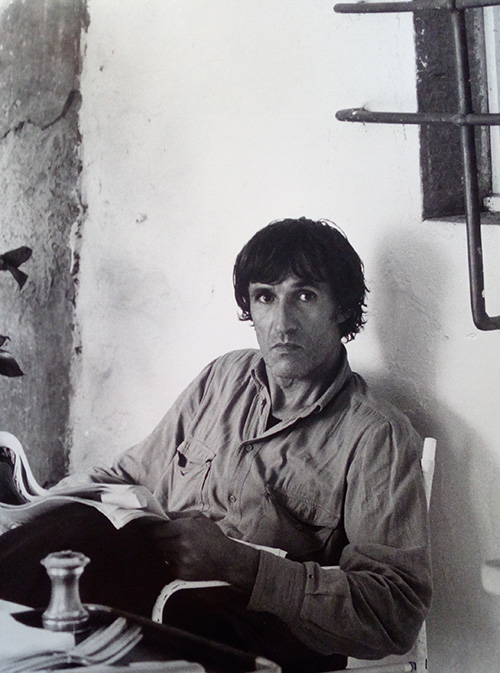

Boetti in his studio, 1974, photo Antonia Mulas

AB produced MILLE, Quadratura del Mille, TRENTUNO PER TRENTUNO PIÙ TRENTANOVE, Pari e dispari, Storia naturale della moltiplicazione, explaining:

“Unlike the logical and unambiguous progression of addition, multiplication proceeds by a twofold mental process: the growth within each form corresponds to an equivalent growth in the number of forms.”

Alighiero Boetti, 1974, photo by Antonia Mulas

These works were all drawn in pencil by the artist and then gone over in black ballpoint by his assistant Mariangela De Gaetano. The first were exhibited the following year.

The works in embroidery were performed at the same time as the works in ballpoint. In fact, starting from Ordine e disordine, he used many phrases in both strands of his work, even in the course of the eighties, as was the case with Dare tempo al tempo and Ammazzare il tempo.

AB began to produce his first Calendari, by selecting from the 365 sheets of an ordinary astronomical calendar only those containing one or more numbers which could be used to compose the digits of the new year, a figure that determined the variable number of works he could produce. Greetings gifts created exclusively for his friends, they gave rise to a tradition which he continued until his last new year.

Alighiero Boetti, 1974, photo by Antonia Mulas

1975

At the start of the year Boetti took part in the group exhibition “24 ore su 24 ore” at the Galleria l’Attico run by Fabio Sargentini, exhibiting fifty drawings of Bombe ordigni origami e altro traced on extra strong paper, Estate 70 (the roll 20 meters long which he made in 1970) and some photographic enlargements of jokes about contemporary art clipped from newspapers and collected under the title of Riso (“Laughter”).

Alighiero Boetti with Annemarie Boetti, Agata, Matteo and Salman Ali, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In January and February he spent a whole month in New York with his wife, children and Salman Ali preparing his exhibition at the John Weber Gallery. They stayed in a loft at 10 Bleecker Street in the Tribeca district. He made friends with LeWitt, Weiner, Kossuth and Bochner. This was his second solo exhibition at the gallery. It opened on 8 February, with two large works on squared paper, Storia naturale della moltiplicazione and Trentuno per trentuno più trentanove. The exhibition was accompanied by an offprint of Tommaso Trini’s 1972 text, “Come non deragliare parlando di Alighiero Boetti.” Trini himself reviewed the exhibition in the June number of Data. The only American review, by Susan Heinemann in Artforum, was very critical.

Weber also organized a seminar for the artist at the Art School of the University of Hartford, where AB did some performances, including Due modi diversi di fare due cose diverse and Raddoppiare dimezzando. Attempts to persuade New York University Press to publish the Libro dei Fiumi in an English version proved fruitless.

Alighiero Boetti prepares the 42 bombs, photo by Giorgio Colombo

On returning to Italy, Annemarie Sauzeau reflected on the experience of three years of America (the Galleria Weber, MoMA, universities and publishers) and wrote to their faithful friend John Weber: “Our conclusion after New York, for example after reading the reviews of exhibitions, is that Alighiero’s work and he himself are not understood in America. You are an exception because you have understood him, and that’s wonderful. I say this without indignation, it’s all for the best and things will change. I’m only referring to the current situation…”.

In May, Boetti had a solo exhibition at the Galleria Pasquale Trisorio in Naples: “boetti 1966.” It presented works from the Arte Povera period: Scala, Sedia, Mancorrente metri, PING PONG, Zig Zag, Mimetico, panels with words: CLINO, stiff upper lip and the triptych on cardboard 01.130 verde vagone, 1133 rosso adrianopoli, 2233 bleu positano.

In Munich, the Area Gallery presented a small solo show, “Zwei,” dealing exclusively with the theme of the double. The catalog was edited by Bruno Corà. The exhibition was repeated in November in the Florence venue, with the addition of a reading from the Koran, his favorite objet trouvé. He had bought a number of copies in Kabul to give as presents (at times with his name engraved in them). In June a solo exhibition at the Galleria Sperone in Rome again presented Storia naturale della molteplicazione.

Alighiero Boetti at the Banco / Massimo Minini Gallery, 1975, photo by Ken Damy

In the summer Boetti traveled widely in Sudan and Ethiopia, sending back his postal works, which included Codice, Eritrea libera. He reached Harrar, as a tribute to Rimbaud in Abyssinia. Three years later he recalled:

“Rimbaud arrived in Africa by ship. That certainly was an adventure. In 1975, when I was in Ethiopia, a boy asked me in English if wanted to see Rimbaud’s house. I asked who he was. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘a person who gave French lessons.’ I realize the imagination now offers nothing like that ship that carried people towards new horizons.”

In October at the 13th São Paulo Bienal in Brazil, he was represented by Storia naturale della moltiplicazione. It was chosen by the commissioner for the Italian participation, Bruno Mantura.

In September he intensified the reordering, begun in ’73 with Rinaldo Rossi, of the profusion of his drawings, photographs, performances and ideas, to complete the portfolio Insicuro noncurante. It was presented on 23 October at the Saman Gallery in Genoa. A drawing made up of dashes and crosses on squared paper, originally titled I pini non crescono in un giorno, underwent further development. In the folder Insicuro noncurante it was inserted with the outline doubled and given the new title Verificando il dunque e il poi se ne andò piano piano verso il canto di una pineta (a quotation from Metastasio). In 1979, transferred to fabric embroidered in white on white, the drawing became L’albero delle ore. Boetti explained the triangular form of the composition in these words:

“The bell tower of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere sounds the hours and quarter hours with two different notes. So at every quarter hour you hear at the very least one stroke (at 1 o’clock) up to a maximum of fifteen (at 12:15). This progression, transcribed into two signs like two notes, forms a double triangle, of day and night.”

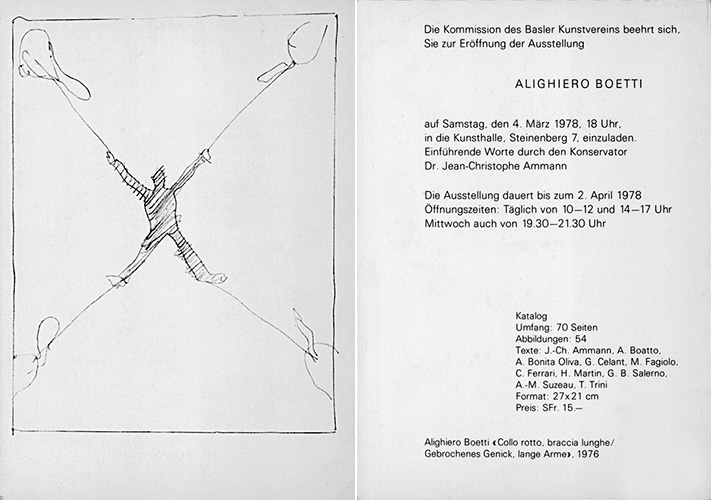

This year there appeared three small drawings: Gradine, a human outline slumped across some steps, Giogare and San Patrick, which were subsequently integrated into two large drawings on light paper, both titled Collo rotto braccia lunghe (1976).

“I did that work thinking about someone who was able to turn his neck 360 degrees—a broken neck obviously—and then I thought about the blind person interviewed by Diderot on the problem of blindness. Diderot was obsessed by this problem, he’d done a whole book about the blind. He interviewed them, asked them what a mirror was and so on. He asked one if would like to see the moon and he replied no, but he’d like to touch it, to have hands so long he could touch it…, the desire to touch from afar…”.

The Boetti completed Classifying, the thousand longest rivers in the world. While continuing their search for a publisher, AB prepared to transfer the list to fabric with a view to having one or more tapestries embroidered in Kabul with the title I mille fiumi più lunghi del mondo. In preparation, he designed three small test pieces and had them made up over the same years. They showed the names and lengths of the rivers written in “pixels,” which would be embroidered in three color variants. In the two large definitive versions, begun in ’76, the entire list of rivers unfolds in horizontal lines about five meters long, arranged in descending order (from the longest, the Nile-Kagera, down to the thousandth, the Agusan).

Alighiero Boetti with some of his works on deposit at the Galleria Banco / Massimo Mini, Brescia, photo by Ken Damy

Through Francesco Clemente, AB met Giovan Battista Salerno, a young art critic with whom he formed a strong and enduring intellectual affinity. Between his other friendships that with Mario Schifano, whom he had met in his early years in Rome, was strengthened. Of their relationship, Salerno observes: “I believe that Alighiero respected a certain eclectic freedom in Schifano, the fact that he went in for cycling and Polaroid photos! Eclectic, not amateurishly but as an encyclopedic way of drawing on practically everything, from movies to parties or bicycle design. I think it brought them close together.”

1976

The magazine Studio International55 devoted the whole of its January–February issue to Italy. Titled Italian Art Now, it had an introductory essay by Achille Bonito Oliva (“Process, Concept and Behavior in Italian Art”) and contributions by Germano Celant, Annemarie Sauzeau Boetti, Barbara Radice, Caroline Tisdall and Luca Venturi. The artists chosen were presented with illustrated interviews or with four pages edited directly by each. Of Boetti’s pages, the first two (a photo and eight small drawings) were figures from the Insicuro noncurante portfolio.

The third page was titled “Classifying the Thousand Longest Rivers in the World, 1970–1974, a book by annemarie and alighiero boetti” and was a typed list of the one thousand names of rivers in order of decreasing length, with some corrections in pen. Finally, on the fourth page appeared a photograph of Estate 70, described as “summer 1970, a roll of paper 20 × 2 meters, self-adhesive dots in 4 colors.”

The portfolio Insicuro noncurante was presented in March at the Studio Marconi of Milan and in May at the Galleria D’Alessandro-Ferrante in Rome. Boetti then suggested that Giovan Battista Salerno should start work on an informative manual about the portfolio. Of the project, Salerno wrote: “From the start we planned to do an ‘informative manual’ together. What he hoped was to have a brief text ‘for each work’ which would be neither a critical reading nor just journalism nor yet information pure and simple, but all these things together. It should help its viewers to lose a little less time as they looked by dwelling on the aesthetic or purely formal side of the work. Because though this part was present and in fact striking, there were other things that at times suddenly clicked in the viewer’s mind but were not always so obvious, certain devices or codes…”.

Salerno also wrote the text presenting the portfolio in the bulletin Studio Marconi n° 5.

In October the exhibition “Prospect Retrospect, Europa 1946–1976” was held at the Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf. It was curated by Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Rudy Fuchs, Conrad Fisher, John Matheson and Hans Strelow. Boetti was represented by recent works on squared paper.

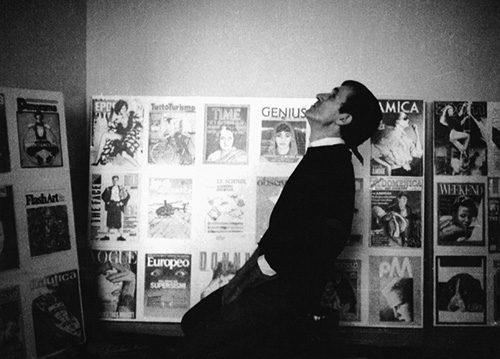

A few days after Düsseldorf, the solo exhibition “quadrare diagonando. alighiero e boetti” opened in Brescia at Massimo Maninni’s Galleria Banco. “Quadrare diagonando” referred to a small drawing (which had already appeared in the portfolio Insicuro noncurante) printed on the invitation. It also appeared in one of the works on display among the thirty-six graphic symbols of Gli anni della mia vita.

Two hands a pencil, photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni

The Brescia exhibition marked an important stage in the development of Boetti’s art, presenting works which revealed an increasing complexity. This appeared in the parallel typologies of La notte da luce alla notte, a ballpoint pen from ’75, La metà e il doppio, a drawing in India ink on squared paper, and an Autodisporsi, both from ’74. On display was Prima e quarta di copertina, one of his first montages with tracings of cover designs. They looked ahead to the large series of images based on popular magazines, a recurrent theme in the eighties. Finally he designed a poster for the gallery using a sequence of black and white photos taken by Gianfranco Gorgoni in ’75, in which we see the arms and hands of the artist as he traces a pencil line on a sheet of paper. The image, subsequently titled Due mani, una matita, was also described by the artist himself as “Two limbs and a pencil.” Another similar shot by Gorgoni immediately became a pencil drawing, Senza titolo, which was the matrix for the whole sequence of works on paper Tra sé e sé.

1977

On 16 February, the Marlborough Gallery in Rome presented “Alighiero e Boetti”: it exhibited Niente da vedere niente da nascondere (1969); 720 lettere dall’Afghanistan (1973–1974); a work in biro, Segno e disegno; Collo rotto braccia lunghe (1976) and the ink version of Gary Gilmore (1977). The artist’s attention was captured by violent deaths in the social context of the so-called “anni di piombo”: AB traced the outlines of various corpses among which Pasolini’s; also Gary Gilmore, who was under death sentence in the USA but asked for immediate execution, moved him particularly.

“For three days, using my left hand, I wrote out his interview, his last moments, when they forcibly put the hood on him, because they couldn’t look at him any more. He was my age.”

On the same occasion, at the Marlborough, he presented Orologio annuale (a GEM Montebello limited edition wristwatch issued in 200 numbered examples). He also began another ritual, rather like the Calendars begun in 1974, a new annual appointment with Contatore, a “time counter.”

Annual Clock with preparatory drawing, photo by Giorgio Colombo

Between February and April, the Galerie Annemarie Verna in Zurich presented a solo exhibition divided into two parts. The invitation was a page in black and white with a detail from Gli anni della mia vita dating from ’75. The works exhibited in the first phase were the set of panels of the Insicuro noncurante portfolio and an unpublished drawing Vista dallo studio (a composition that eventually became Tracce del racconto in the group exhibition at San Remo the following December). The second part of the exhibition presented, on its own, the work in ballpoint pen, I sei sensi, on eleven sheets of blue paper.

At the same time, in Florence, the Galleria La Piramide Multimedia presented works by AB essentially on squared paper, including Autodisporsi and Alternando da uno a cento e viceversa. The artist commented on them in these words:

“I called up a boy in Milan and explained a system to him: take a hundred squares made up of a hundred smaller squares each and alternate one black square with two white squares and so on. He did this, sent me the sheet and the work was ended and at the same time begun. In this way I eliminated the problem of ‘quality’: whether this work is done by me, by you, by Picasso or by Ingres doesn’t matter. It’s the leveling of quality that interests me.”

The artist also arranged for an embroidered version to be made of the work. This was one of the phases of this arithmetical theme, and not the last.

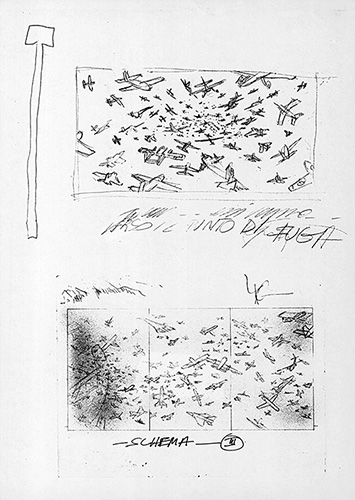

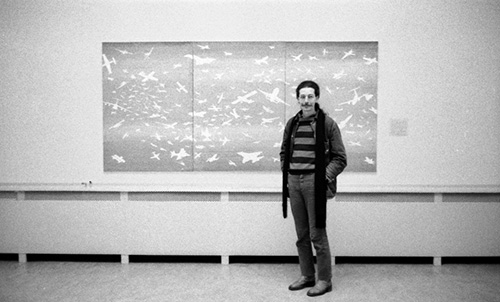

AB was working with the designer Guido Fuga on the project for the Aerei triptych.

“There is a firm in Turin which sells a cheap four color print in strips of an exotic landscape. I’d like to do something similar. I want to get an assistant to draw a thousand airplanes on a sheet of paper with a dark blue ground, the color used for the sky in nativity crèches. The planes accurately drawn in all different perspectives, from different angles, so they look really stunning. It has to be explosive!”

On 31 March, he had a solo exhibition at the Galleria L’Ariete in Milan. The works included the two recent drawings Gary Gilmore e Collo rotto braccia lunghe, Alternando da uno a cento e viceversa (drawing on squared paper) and a postal work. In the adjacent room, Ariete-Grafica presented: Orologio annuale and the “edition” of two small embroideries (Per nuovi desideri and Udire tra le parole) made specially for the gallery.

Preparatory drawings Aerei di Fuga

It should be noted that the term “edition” has a specific meaning in relation to AB: it is always a sequence of unique examples, which he himself called “single multiples” because they were executed by hand and inevitably with different features, from the colors to the single “hands.” This was true not only of the embroi- deries but also other types of works.

The Galleria L’Ariete also exhibited some examples of the poster Faccine printed in offset. The magazine Data (number 26) published the image full page with this caption: “Poster measuring 140 × 100 cm, published by the Multhipla in Milan, and printed in 5000 copies in black and white.

Some of these posters were then given to be colored to the children at the Casa del Sole school, and then exhibited in the gallery. The black and white posters on sale in the gallery cost 3000 liras, those colored by the children cost 5000 liras.” Other copies of the poster were then given to friends and collectors with the invitation to color the drawing.

In April, on AB’s eleventh visit to Afghanistan, he was accompanied for a month by his seven-year-old son Matteo.

On his return in May, he participated in the Turin group exhibition “Arte in Italia 1960–1977” curated by Barilli, Del Guercio, Menna, at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna. He displayed Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione. The work was not recent but perfectly aligned with the theme of the section curated by Renato Barilli, titled “From the Work to Involvement,” from the neo-Dada legacy down to Arte Povera and the beginnings of Italian conceptualism. Barilli wrote: “Boetti has already explored certain serial and combinatorial possibilities. However unlike the serial works of minimalist inspiration, his always entail intervention by others.”

AB continued to produce works in ballpoint, in sequences distributed on a number of sheets of paper (as in Seguire il filo del discorso, which was done on five sheets), as well as designing new medium-sized embroideries for Kabul (measuring about 50 × 60 cm) bearing long, poetic inscriptions: Sandro Penna io vivere vorrei addormentato entro il dolce rumore della vita, Verificando il dunque e il poi se ne andò piano piano piano piano verso il canto di una pineta (a quote from Metastasio) or Ordine e disordine, done in white on a black ground.