1992

November 14, 20171994

November 14, 2017AB planned to make seven bronze copies of the Self-portrait, a complex sculpture conceived twenty years before. Three were made in ’94, the others only later. In June, the first example was presented at the exhibition “Sonsbeek 93” and permanently installed in the park of the Dutch museum in Arnhem.

In the studio AB designed a “classical” carpet of the Persian type that was to become the summa of all his iconography. He delegated the production of samples and the final cartoon to his new assistant, Simone Racheli. The work was entrusted to his usual weavers in Peshawar, who were still busy with the khilim. This large carpet (350 × 240 cm) was to be the last work that returned from Pakistan after the artist’s death.

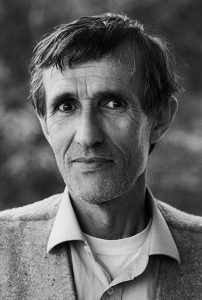

Alighiero Boetti, 1993

In March, a solo exhibition was held at the Galleria Christian Stein in Turin. The exhibits ranged from his very earliest works in 1966, never exhibited before, to some that were present in his first solo exhibition in ’67. This was to be AB’s last solo exhibition in Italy. Christian Stein had also presented his first.

He was busy with numerous other exhibitions, especially in France. For example “De la main à la tête, l’objet théorique” at the Domaine de Kerguehennec in Brittany and the Lyon Biennial titled “Et tous ils changent le monde.” Besides the preparatory work for Grenoble, AB was busy giving concrete form to his dialog with the artist Frédéric Bruly-Bouabré with a view to organizing a joint exhibition, scheduled for 1994 in New York.

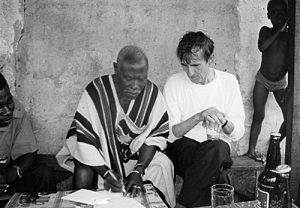

“We brought the two artists together for the first time in Paris in March ’93. We were struck by the way they clicked and the warmth between them. While the project was being worked out with a view to an exhibition it was decided that each would call on the other ‘at home.’ It could have led to a true collaboration to extend the dialog envisioned between specific works. With his family Alighiero went to Abidjan, where Bruly lives today, and then the village of Zepreguhe where he was born.”

Alighiero Boetti and Frédéric Brouly Bouabré, Abidjan Ivory Coast, photo by Caterina Raganelli Boetti

AB’s stay in Ivory Coast, with Caterina and little Giordano, proved highly problematic for various contingent reasons. AB had difficulty relating to African culture, but with great intellectual honesty he was able to recognize the distinctive qualities of his friend’s work:

“There is a time for the great attractions… My attention was wholly turned to the East, the mountains of Tibet, tea, the Zen monks and their gardens… In Paris I happened to encounter African art, but I do not feel a particular interest in it. It’s extraneous to me on the emotional level, I’d say.

I can admire certain qualities, like its intensity, but it’s at a kind of distance from me… In the case of FBB it was the opposite. With his postcard format and the temporal continuity in his work, he can focus his attention anywhere, he can do anything. He speaks an essential language and deals with everything… But the basic idea is the same: to create a system, a world in which his discoveries about life, his marvels, can be reproduced, bringing out the phenomenal potential of our brain, our imagination.”

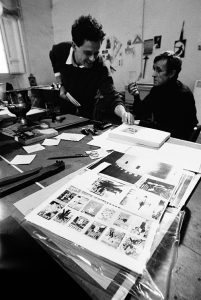

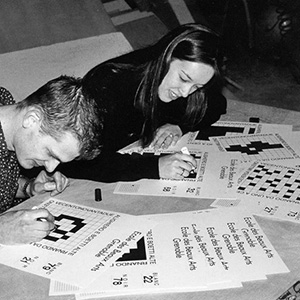

AB in the Pantheon studio with Andrea Marescalchi, known as Bobo

In June, at the 45th Venice Biennale, in the Italian Pavilion, AB exhibited the large banner made for Gibellina in 1985. In the same period he was represented in the collateral event “Trésors de voyage” curated by Adelina von Furstenberg, installed in the Armenian monastery on the island of San Lazzaro. His project documented the artist’s passion for the production of books, all bound in red cloth. Classifying the thousand longest rivers in the world of ’77 and numerous later volumes down to 111 were subtly introduced and camouflaged in the Armenian fathers’ library.

Boetti systematically requested curators of his exhibitions to adopt the style of his “red books” in their catalogs from 1990 on. An example is the catalog of the exhibition at the Galerie Kaess-Weiss in Stuttgart (1990), Accanto al Pantheon, published by Prearo (1991), and another for the traveling exhibition presented in Bonn, Münster and Lucerne (1992–1993). Later he added the catalog of De bouche à oreille of the Magasin of Grenoble in late ’93 and the complementary volume published by the Musée de la Poste and devoted to the major Lavoro postale in early ’94.

Even after AB’s death, as a kind of tribute to his predilection, other catalogs were issued in the same style.

Among the artists participating in “Trésors de voyage,” AB again encountered Bruly-Bouabré and, as previously agreed, confirmed the invitation to stay in his farmhouse in Todi. Unfortunately, in summer AB was diagnosed as having tumors in the lungs and head, seriously jeopardizing his work.

The preparatory work of the kilims, made by Fine Arts students in France

On 26 October, in Paris, his sculpture Self-portrait was installed as a point de mire in the great lobby of the Centre Pompidou, while in Rome AB, working frenetically, completed preparations for the complex exhibition in Grenoble. Fundamental to the success of the project was the extraordinary personal commitment of Adelina von Furstenberg. At the beginning of the catalog she paid a heartfelt tribute to the artist, with a Sufi parable about a khilim. Between the curator and the artist there was not just a close friendship but also a special elective affinity for the culture of central Asia. “Giovanni Battista Boetti was an ancestor of Alighiero Boetti and also a Sufi of the order of the Masters (Khwajagan), founded by the Master Naqshbandi of Bukhara. I came across a story which Naqshbandi used to tell his disciples to illustrate the ‘hidden dimension’, through the quest for knowledge.”

The 50 kilims at the “De bouche à oreille” exhibition at the Magazin de Grenoble, November 1993, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In the same catalog the curator, Angela Vettese, presented a cultured repertory of images, reflecting the many-sidedness of AB’s artistic development and in particular his Pensato e quadrato series: cosmic combinations starting from the Hebrew alphabet, Japanese manuscripts, medieval poems, the incipit of Mozart’s Danse Allemande, the “magic square” studied by Blaise Pascal and the Chinese ideogram for the plenitude of the void.

With great fortitude AB succeeded in being present at the opening ceremony in Grenoble on 27 November.